Heaven and Hell

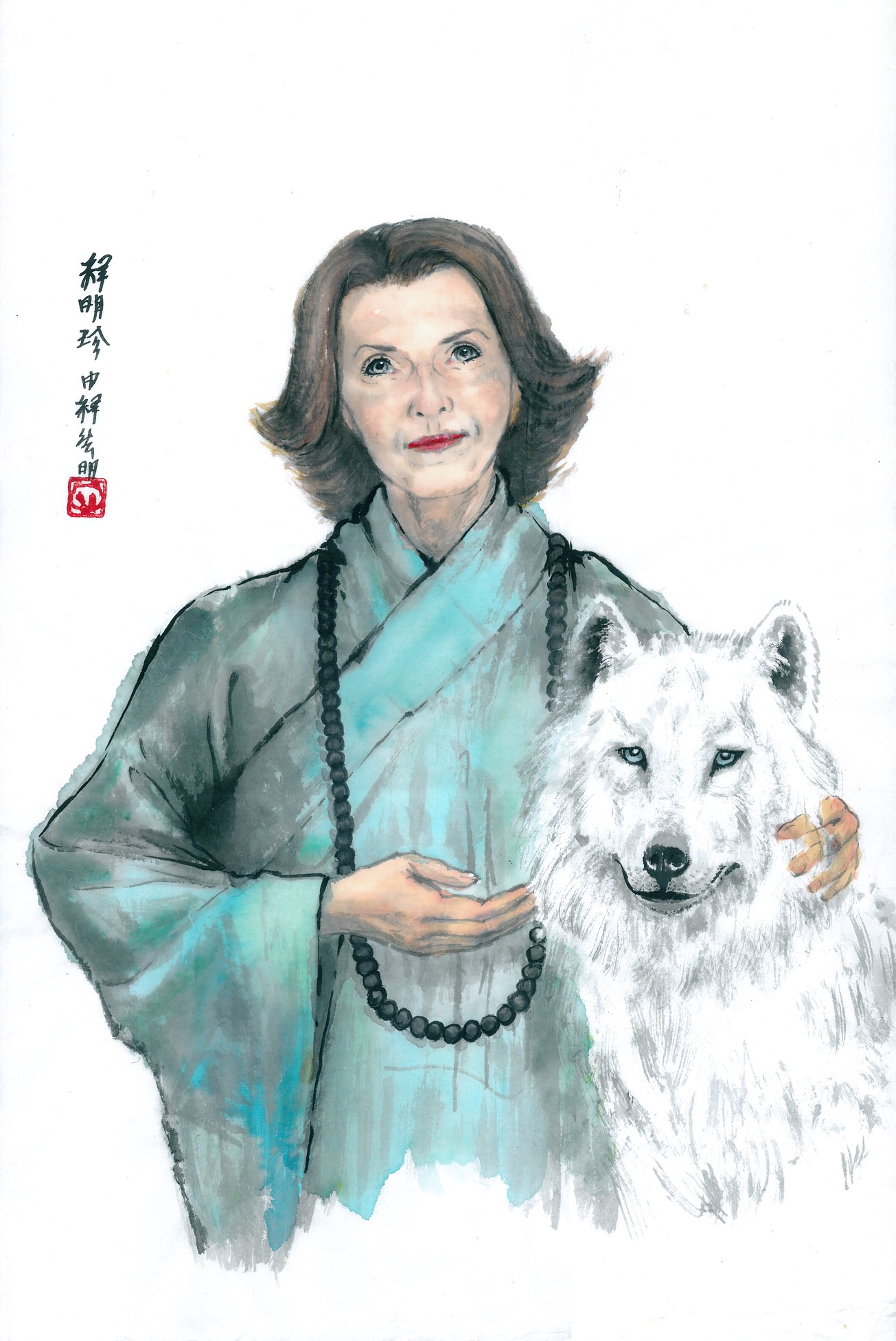

by Ming Zhen Shakya, OHY

I wish I didn’t enjoy my prison ministry so much. If it were less agreeable I could make myself seem like a martyr for making the trip out to Jean every Wednesday.

But the fact is, I like going there. It keeps me on my toes. Every cleric is a philosopher of sorts and prisons are often the true enclaves of philosophy. The men don’t have an awful lot to do in their free time. So they think and then discuss what they think and then, I think, lay intellectual traps for me to see what I think.

The subject of heaven and hell came up recently. One of the men quoted Milton to me…. or threw him at me, I should say. “‘Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven,'” he challenged. “Geez,” I said, responding with the standard comeback, “What makes you think that if you go to heaven you’ll be a servant but if you go to hell you’ll be a king?” And he countered with a certain, histrionic flair, “If? If I go? I am in hell.” And after the others stopped grunting in affirmation, I said, “Well, Your Majesty, there you may be, but not for the reasons you think.” And then I had to start thinking about reasons and as I say, it keeps me on my toes.

Fortunately, he had picked the best known passage in Milton’s Paradise Lost. Had he been more esoteric in his reference, he might have made me switch subjects… after all… I haven’t read the whole of it. He probably had… but then it would pretty much take a prison term — I’d better quit before I offend Milton lovers.

“Well,” I said with a sizzling riposte, “just before Satan said that, didn’t he say something about the mind being its own place and inside itself could make a heaven of hell and a hell of heaven?” This equally famous line constitutes, you see, the core belief of Zen Buddhism. We can’t help it if Milton put the line in Satan’s mouth. Satan surely can get a few things right. As they say, even a stopped clock is correct twice a day.

Then, to illustrate the point I was trying to make, I invited the men to play a kind of game and tell me what I was describing: I said, “I see a group of buildings surrounded by a high wall and a locked gate. The inmates wear uniforms of plain, coarse material. They eat simple food, prepared without garnishment or sauce. They rise early and retire late. Everywhere they go and in everything they do, they are subject to someone’s absolute authority over them, and to endless rules and regulations and punishments for breaking same. They are expected to work for many hours a day and to keep silent for many other hours. They have virtually no freedom of choice. They sleep in rooms called cells, and when they retire to their beds at night, they are alone… for no female companionship is allowed them. OK,” I said, “What am I describing?”

I didn’t fool any of them. “A monastery,” they all answered, and we laughed because it is funny the way a monastery headed by an abbot and a prison headed by a warden are so strangely similar in design. But there the similarity ends. The obvious difference between monks and convicts is that the former desire to live under such conditions and are usually happy and the latter are forced to…and are usually miserable. The conditions are the same. The state of mind… the desire… is different.

Zen has a very pragmatic approach to the subject of heaven and hell. We recognize them as two states of mind that can be experienced in the present moment. Regardless of whatever happens at the end of life, Nirvana and Samsara, our earthly states of Heaven and Hell, can be experienced right now while we’re still breathing.

According to Buddhism’s Four Noble Truths, life in the world of the ego, which we call Samsara or Hell, is bitter and painful. No argument there. And the Second Noble Truth is that the cause of this bitterness and pain is egotistical desire. And isn’t that the difference between monks and convicts? One group wants to be where they are and the other doesn’t. The question is why… specifically why do monks want to be there? If you ever spend any time in a monastery, you’ll likely ask yourself that question a few times a day.

But the answer is really quite simple. The monks are seeking heaven and they’re trying to qualify for gaining it. They’re turning their attention inwards – away from the world – because they wish to become One with the King who reigns there, in that Kingdom that lies within. And before they can do that, they must learn to serve that King with unconditional love, in egoless humility and purity. The convicts were still living in the world of desire.. the one presided over by Satan or Mara – to use his Buddhist name.

What is the nature of this desire that in seeking its satisfaction they, and we, create such hells for ourselves? Back in 600 AD Saint Gregory listed the Seven Deadly Sins and they’re still very much alive and well – even after Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman got finished with them. Those seven universal expressions of egotistical self-indulgence have lost none of their virulence: pride; greed; jealousy; lust; sloth; gluttony; and anger. The mind that is infected with any or all of these Seven Deadly Sins is attached to, i.e., is emotionally engaged by desire or aversion to the people, places and things of this, the ego’s, world. This ego-mind wants to be loved and admired, to be feared and respected, and to indulge itself in a variety of sensory pleasures; and it doesn’t much care what it has to do to get what it wants.

If Zen’s goal had to be stated in a single word that word would be non-attachment… freeing the mind from its fixations on the things of the outer world and turning it inward, to its relationship with God or the Buddha Self. And it doesn’t matter whether you are housed in a monastery or a prison since the accomplishment of this goal depends not on the nature of the real estate, but on the nature of the heart.

I’ll close this little Dharma talk by relating one of Zen’s favorite stories:

There was once a very proud and powerful king who fancied himself a philosopher. After much disputation and argument, mostly with himself, this King reached the conclusion that there was no such thing as heaven or hell. These were mere superstitions, he decided, and he therefore decreed that henceforth there would be no further talk of heaven or hell in his kingdom. Anyone who defied his Royal Will by even mentioning them would be severely punished.

One day a holy man visited the kingdom; and despite numerous warnings, this holy man began to preach about heaven and hell. Naturally when the king heard about it he was furious and ordered the man arrested and brought to court.

“Everyone knows that my conclusions are correct,” the king said to the holy man. “Why do you persist in preaching a doctrine that is so obviously false?”

The holy man sneered and laughed at the king. “Do you expect me to discuss philosophy with a buffoon like you?” he asked.

Instantly the king was on his feet! Enraged, he shouted at his guards, “Seize him!”

Then the holy man raised his hand and said, “Sire… Sire… Please… One moment! Understand! There is a hell and right now you are in it!”

Suddenly the king understood! He saw himself standing there, burning with rage, consumed with violence and contempt; and he understood that hell wasn’t a place where the body burned, but where the spirit burned.

And horror-struck by his own actions, he sat down on his throne and trembled and covered his face with his hands. And when he finally looked up again, he was filled with love and gratitude, and the wonder of enlightenment.

Quietly, he said to the holy man, “And to think of your great generosity in teaching me this! To think how you risked your life just to enlighten me to this truth! Oh, Master! Please forgive me.”

And the holy man said, “And you see, Sire, there is a heaven, and right now you are in it.”