And now if any be ignorant, let him be ignorant. I know not what more to say and not transgress the Silence of Pythagoras.”

– Sir Isaac Newton, Alchemical manuscript, The Regimen

(MSS 1032B RB NMAH, Smithsonian Inst.)

Spiritual Alchemists never attempted to cut God down to size and turn him into a lawman they could bribe, trick, cajole, or outdraw. They were always mindful of the Ground of all Being, of the Supreme God of all those lesser gods with whom they had to struggle each day of their lives. No taint of immorality colors the records of their investigations: Newton, Ashmole, Ripley, Boehme, Paracelsus, Avicenna, Dorn, Meier, et al., were good men of unsurpassed intelligence; but they, who could see, were ever mindful to get out of the way of the blind. The cruel prejudices of lesser men always threatened their well being; and for this reason alone, they were secretive in their pronouncements and cryptic in their writings.

Even as far back as ancient Egypt’s alchemical regimen, personal integrity and ethical conduct, striven for, achieved, and maintained were mandated for anyone who wanted to reach the divine journey’s destination. Natrium or no natrium, a heaven-seeking soul still had to be questioned by Osiris about its earthly conduct; and that soul had better be able to give the right answers.

And so, according to custom, whether a person intended to enter heaven before or after death, he couldn’t rely upon a priest’s absolution or the purchase of indulgences. Then, as now, the best way to deal with sin was to avoid it; and the best way to avoid it was by avoiding those with whom one might be tempted to enjoy it. It was both ironic and fortuitous that the same suspicion of sinister activity which forced an alchemist into seclusion also provided him with the ideal conditions for creating an environment which did not conduce to moral error.

While the uninitiated soul would look to an external god to praise or blame according to his blessing or misfortune, the alchemist was required to look within himself to find the cause of pleasure or distress. As the gods were in the macrocosm, so they were in the microcosm. They were inside him and he had to deal, one-on-one, with them and their impulses. The assistance he needed to gain some measure of control and some understanding of their unpredictable natures he obtained by projecting divinity into substance and then operating on the substance. This was a completely new theo-psychology. It seems odd to us now to think that intelligent people could so ingenuously imbue matter with divinity, but we must consider chemistry’s mystique. Nobody understood chemical reactions; and so, for as long as these reactions were so confoundingly mysterious, they were a blank sheet upon which any imaginative explanation could be written. We who have ‘miraculous’ medals and charms of every kind and who read our horoscopes every morning should not find it all that strange that these intelligent people saw mercurial behavior in mercury.

But chemicals were only part of the alchemical path. Just as a tennis or hockey player practices diligently to perfect his skill and does not rely upon lucky caps or songs, the alchemist, as well, did not limit his labors to contemplating the mysteries of those chemical reactions he caused and observed in his laboratory. Again, as it was in the laboratory and the cosmos, itself, so it was within his own body; and before the precious metals could be infused with a usable divinity, just as they had to be mined in some mountain’s drift or shaft, they had to be mined in the earth of what we now call Muladhara (root chakra); as they were bathed in a sluice, so they were rinsed in the waters of Svadhisthana (sacral chakra, dantien); and then they were smelted in the crucible of Manipura (solar plexus, personal energy). This took heat; and the Yoga of the Psychic Heat, known to every shaman on the globe, had to be accomplished to furnish the fire, the requisite spinal conflagration. The alchemist had to be a yogi, a master of fire.

If this were all there was to it, the functions of these lower chakras or “wheels” would not have mandated such secrecy. The alchemist needed salt – the body’s own natrium – as part of the vital compound; and he obtained this salt, often called the Prima Materia, from seminal fluid which he figuratively “circulated and distilled.” This was the true discipline: acquiring proficiency in meditation “on seed.”

An array of actual and imaginative operations had to be performed on the mixtures of energies obtained from the earth and air, from a variety of body fluids, and from the representative chemical substances. Phases of the work received such color coding as black (nigredo), white (albedo or leukosis), yellow (cinitritas) and red (rubedo). Sulphur was a Sun substance which turned blood red when heated; metallic iron rusted to martial red; copper oxidized to green which naturally became Venus’ color. An iridescent patina which formed on oxidizing silver became Diana’s Doves. The spiritual work was further encoded in such procedures as, “Calcination, sublimation, solution, putrefaction, distillation, coagulation and tincture,” or as “Dissolution, maceration, sublimation, division, and composition,” or as “Dissolution, purification, introduction (into the furnace), solution, putrefaction, multiplication, fermentation, and projection.” There was no end to the terms and no consensus among those who employed them. It was metaphorical chemistry… or chemical metaphor.

In concert with external laboratory experiments, the work of “circulating” seminal fluid initiated the internal, “spiritual” Opus proper, and, inasmuch as the fluid figuratively constituted the main substance of the Philosopher’s Stone, the Immortal Foetus, it also marked the work’s terminal phase. But before the Lapis could be produced, many degrees of achievement had to be attained. The worker started as an apprentice, went on to journeyman capability, and finally became an adept, a master. Meditational disciplines had to be learned, and the requisite morality acquired; and there were also certain stirrings in the cauldron of the collective unconscious that had to be felt – certain agitations that had to be calmed. Gods projected out into the world had to be withdrawn from society and restored to the “bottle” of the mind; even as the alchemist himself had withdrawn. And even after all his work, he could not force the most important event of the Opus to occur: Divine Marriage or the Rebis Experience. This crucial experience, which in Zen is called The Union of Opposites, was granted through Grace, alone. The idea that the event could be bypassed and the Divine Child produced without benefit of a maternal parent, may be acceptable in cloning circles, but nowhere else. Even Divine Children must have two parents: one mortal (the alchemist) and one Divine, his Anima or Bodhisattva. Divine Marriage, in Jungian terms, is the stupendous event called Integration of the Anima/Animus.

Integration of an archetype, as we will later explore, is not mere withdrawal of an archetype. Just because a man is not at the moment in passionate love with a woman and has therefore got his Anima residing in his psyche does not mean that he has integrated her. The man, perhaps as a result of heartbreaking loss, may say, “Never again!” which then makes it almost a certainty that there will be an “again.” Such utterances are consciously made pronouncements – thoughts expressed; and therefore they constitute hubris of the worst kind. (No human ego can tell the powerful inhabitants of the collective unconscious how they shall or shall not behave. Archetypes are instincts and instincts have minds of their own and regard themselves as being utterly divine. A true “never again” is beyond thought, it is of an action that is ‘unthinkable’. )

Merely withdrawn, a goddess behaves like a tiger in a straw cage: she paces, only temporarily inconvenienced, and amuses herself by making the man prissy, overly fastidious, moody and capricious – a caricature of femininity. Then, when she desires – and not until she desires – she will escape to drape herself upon some mortal woman before whom the man will kneel in worship. And the man finds himself wonderfully in love again, for as long as the divine illusion lasts.

An integrated love-goddess, his true soror mystica, has a life of her own in the “other” world which she allows the man vicariously to enjoy whenever he enters the meditative state.

Jung called the method of entering this meditative state “Active Imagination” which is probably the worst term he could have used since it suggests daydreaming and not a disciplined entrance into a Mandala’s sacred setting. The ego does not direct other-world actions. It witnesses them but does not alter them. They, on the other hand, alter his consciousness. The beauty of the old alchemical opus, at any of its levels of achievement, was precisely this: that in the act of projecting characteristics and events upon surrogate chemicals, an alchemist acted and reacted unconsciously. Entranced, he was suggestible.

As we now employ the term ‘alchemy’ it indicates all the various methods of spiritual discipline; the original alchemy, however, required much more in the way of obedience to Sympathetic Magic’s Laws of Similarity and Contagion. For this reason, once the science of chemistry came fully into being and chemical substances lost their mystique, it was no longer possible for a practitioner to bring the same kind of involved enthusiasm to the various tasks. Still, by avoiding such demystifying academic inquiries, the alchemists were able to pursue their programs. We cannot read Isaac Newton’s handwritten accounts of his observations of chemical operations in which he refers to “the menstrual blood of a sordid whore” or “cream of Virgin’s Milk” or “sperm of our Mercury” without knowing beyond doubt that he was in fact imbuing chemicals with spiritual character – and was certainly not trying to determine a gravitational constant or solve a problem with fluxions.

Since alchemy involving chemicals was only one of many methods used to attain spiritual goals, the same results could be had, and often were, by people who whose only regimen consisted in taking their religions seriously. They were told to love their enemies; and as difficult as that demand was to fulfill, they fulfilled it and began the great ascent. All of the world’s successful mystics enter the Rebis Experience’s Bridal Chamber; but few of them ever enter a laboratory.

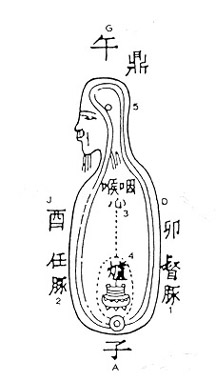

The Microcosmic Orbit showing points A, G, D, J as the four cardinal points. M is the Heart and O is the fire in the “stove.” From: Taoist Yoga: Alchemy & Immortality by Lu K’uan Yu, (Samuel Weiser, Inc.)

The Microcosmic Orbit showing points A, G, D, J as the four cardinal points. M is the Heart and O is the fire in the “stove.” From: Taoist Yoga: Alchemy & Immortality by Lu K’uan Yu, (Samuel Weiser, Inc.)The first stage of the work:

As Jung has noted, two archetypes exist both inside and outside the psyche: the Persona and the Shadow ( in both aspects as Enemy and Friend). Pride and anger, and a certain insecurity that requires the comfort of a best friend-alter ego, evidence these archetypal projections. The Friendly Shadow needs to be integrated so that it can become the guide or companion through the great journey of the Opus, just as Dante had his Virgil and Jung had his Philemon. The spiritual alchemist, likewise, had to be free of anger. Nobody gets anywhere on the spiritual path if he involves himself with friends or enemies, or tries to move forward holding up a heavy Persona, a personally designed mask, behind which he deliberately hides his true face.

Since he must control his ability to enter the meditative state, the practitioner first acquires proficiency in meditation. Again, this state is not the empty-mind state of Quietism. It is a state in which he can concentrate and then, through intense focus of his attention, penetrate the precincts of the Ideal world. He also masters control of the breath and the ability to put his mind “inside” his own body and feel his pulse beating wherever he directs his attention, in particular on the Hara, a point deep in the abdomen where the aorta bifurcates. He learns to control his eye movements in a variety of exercises.

The spiritual alchemist who actually worked in a laboratory would also use chemical reactions as we would use yantras or other objects which engage the eye and the imagination and lead into meditation. (Commenting upon Isaac Newton’s prodigious meditative powers, his assistant said that he’d often leave the laboratory in the evening while Newton sat staring meditatively at an ongoing chemical reaction; and when he returned the following morning, he’d find the old man still staring, seeming not to have moved a muscle during the night.)

Diagram of the Chinese concepts of Golden Flower or Immortal Spirit-body which gives the additional information that, “As there is ample evidence in the text to show that Buddhist influences represented the Golden Flower as coming ultimately only from the spiritual side, that fact has been indicated by the dotted line leading down from shen. However, in undiluted Chinese teaching, the creation of the Golden Flower depends on the equal interplay of both the yang and the yin forces.” From The Secret of the Golden Flower, translated by Richard Wilhelm, (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich).

Diagram of the Chinese concepts of Golden Flower or Immortal Spirit-body which gives the additional information that, “As there is ample evidence in the text to show that Buddhist influences represented the Golden Flower as coming ultimately only from the spiritual side, that fact has been indicated by the dotted line leading down from shen. However, in undiluted Chinese teaching, the creation of the Golden Flower depends on the equal interplay of both the yang and the yin forces.” From The Secret of the Golden Flower, translated by Richard Wilhelm, (Harcourt Brace Jovanovich).In his contemplations, the practitioner would try to understand his own impulses and the actions of others by relating them to the various chemical responses. Artful illustrations and diagrams, mythological tales, wisdom of the East in both the Judaic Cabala and in the remnant practices of mystery religions, and numerous Biblical parables also served to aid such contemplative purpose.

Adam McLean, who has done so much to illuminate ancient alchemical works, in his The Alchemical Mandala, (Phanes Press), comments on a famous illustration which first appeared in Daniel Mylius’ Philosophia Reformata of 1622: “It shows us a mandala centered upon the Tree of the Soul, beneath which an old philosopher is instructing a young knight. They raise their left hands in greeting, indicating the esoteric purpose of their meeting (the left being the ‘sinister’ side of mystical and hidden things). This philosopher is the Wise Old Man within us all, while the Young Man is the explorative, investigative aspect of the soul that seeks enlightenment and quests after the wisdom of the spirit. The Old Man leans upon a staff, representing his long experience, while the Young Man, as if a knight on the quest, bears a sword, a weapon of the intellect, to arm him on his exploration.

Microcosmic orbit showing cardinal points, heart and stove. Taoist Yoga: Alchemy & Immortality, Lu K’uan Yu (Samuel Weiser, Inc.)

Microcosmic orbit showing cardinal points, heart and stove. Taoist Yoga: Alchemy & Immortality, Lu K’uan Yu (Samuel Weiser, Inc.)“Between these two figures stands the Soul Tree, bearing the Sun, Moon and the five planets. This is the realm which the being of the alchemist must penetrate, the seven spheres of the planetary forces in the soul which he must traverse and integrate. He must also bring together the King and Queen archetypes of the male and female forces in the soul, as well as the Four Elements: Earth, and the Fire breathing salamander, on the left; and Water, and Air represented by the bird, on the right.”

To a modern Parsifal, this illustration is particularly significant since it takes the Opus out of the laboratory. We find no flasks and beakers in the drawing.

But what replaces the metals and acids when we are no longer fascinated by the mystique of chemical reaction? “The Goddess unveiled is not the goddess at all,” says an old maxim. There needs to be a seductive curiosity – but about what? Usually, it is psychological trauma that provides the impetus for self-investigation and discovery. We experience bitterness and pain (Buddhism’s First Noble Truth) and seek to find a Way that will free us from such calamity. We are disillusioned and require clarity of vision. The outer world has brought us chaos; and we seek the inner world’s promised cosmos, order. What we need, then, is to become impervious to the manipulations of people and fate. We want to acquire ‘holy indifference’ by which it is meant that we are self-contained individuals who are unaffected by the conditional world’s benefits or injuries.

The Alchemical Mandala: A Survey of the Mandala in the Western Esoteric Traditions, by Adam McLean (Phanes Press).

The Alchemical Mandala: A Survey of the Mandala in the Western Esoteric Traditions, by Adam McLean (Phanes Press).Since the Opus cannot commence until the Archetypes of the Shadow and Persona are withdrawn from the world and integrated into the psyche, it is necessary to determine how, without analyst, laboratory, or miracle, this event can be accomplished.

A few years ago I had intended to write about the Opus and asked an adept, a woman I knew, if she’d share her technique for integrating these troublesome archetypes. Here is her account. I call attention to the peculiar result of this which all of us who follow the Opus can verify: the strange inability to function in groups.

(Recall that members of a group, in deference to their Personas, seek approval and attention from the group leader or, sometimes, even to replace him; and to gain this elevated status, they tend to form factions – projecting the Friend upon their allies and the Enemy upon their rivals within the group. When a person has integrated both aspects of the Shadow (friend and enemy) and has not merely temporarily withdrawn them, he has no archetype available to project and thereby to form attachments or aversions to any faction. He is not neutral, either. We have elaborated upon Buddhism’s peculiar “no and not-no” approach elsewhere; it is sufficient now to say that such a person who has freed himself from the herd instinct is neither neutral nor non-neutral. He simply is not involved.)

I reprint with kind permission the following edited account of the integration of the Shadow and Persona: The writer called it, “My De-Sentimental Journey.”

“I remember my last best friend, a woman with whom I had gone to grade school and junior high school. We could walk to school together, see each other all day, walk home and then in the evening talk to each other for a few more hours. We would giggle hysterically over trifles, wear each other’s clothes, and never have a difference of opinion about music, movies, boys and fashion. We were too young to date, but we did play pinochle on Saturday evenings with a couple of brothers who lived down the street from my friend’s house. We never had any money but neither did any of our other friends so we didn’t notice our poverty.

“My friend’s father had been killed in WWII; and when her mother finally remarried the family moved away to a distant state. Our correspondence dwindled to notes on Christmas and birthday cards; and then, a few years later, married, she moved back to the suburbs of our town, and we renewed our friendship. It was late in the summer.

“To me it seemed as if those years had changed nothing. There was a bond of friendship that had never been broken. Bonds of friendship are more elastic than other bonds. Separation may stretch them a bit, but rarely does it break them.

“Though times were still lean, she and her husband led a well-fed existence; and in this they differed from the rest of our society of old friends, few of whom had achieved any financial success.

“They had a pretty house – an acre of ground around it – two luxury cars and a dog and cat that were both pedigree animals. I remember her scent: she wore Joy by Jean Patou. Her clothes were elegant. She and her husband loved going to Broadway musicals and had the original cast recordings of all of them on vinyl LPs. I remember that her husband would do a great imitation of Eliza Doolitle’s father in My Fair Lady. He’d sing and dance to Get Me To The Church On Time! and those of us who saw him laughed heartily, envious that we hadn’t seen the original stage production. I felt so privileged to call them my friends. Aside from the comfort I found in familiarity, I enjoyed a reassuring pride every time I drove down their lovely tree-lined street and pulled into their driveway. They were by our standards rich and important; and I, alone among our friends, was on intimate terms with them.

“I could see evidence that she was – now I’d call it avaricious – but then I would have called it frugal. Projection’s sentimental trajectory does that to our point of view. What I aimed to see, I saw.

“Yes, I was aware that she was more than thrifty. Everything had a price except the time and effort she spent in determining it. But this peculiarity only added an amusing interest to the portrait I had drawn. I laughed at the way she searched the newspapers for bargains in canned peas or hamburger. I was interested, I suppose, in only those activities that brought us into each other’s company. Aside from occasional lunches, dinners and parties, we regularly – for one season, anyway – played pinochle on Tuesday nights. As in the old days, she and I were partners; we played against her husband and her brother who had come to live with her. We never played for money.

“She and her husband had several small businesses: they sold wholesale lots of jewelry for organizational fund raising, and they also managed the local sale and distribution of a line of specialty baby furniture.

“In those days people were not so mobile as they are today. Those of us who lived in the inner-city had neighborhood stores – groceries, barbershops, notions – shops of this nature; but if we wanted to shop for something unusual, we had to take the bus downtown to where the department stores were clustered. Pregnant women were not inclined to travel; so house parties were frequently given to sell various items such as makeup, lingerie, and baby furniture. One young woman would host the party and invite all her female friends and relatives. She’d receive a gift and a sales’ commission for her trouble.

“Aside from enlisting all our old friends, my friend obtained hostesses by advertising in the newspaper for housewives who wanted to make money at home. She’d offer a respondent a 10% commission on sales plus an additional 5% commission on the sales of anyone else she could induce to hold another party. She sold several items, among them a stroller, a child’s canvas car seat, and her top-seller, a kind of wheeled play-and-eating table. It was a popular item, having a plastic tabletop and a seat that cleverly adjusted to accommodate a growing child. These were rather expensive and could easily cost a few days’ pay. She would come to the party and demonstrate the samples. The guests, enlivened by the strong coffee which she supplied, were always expansive; and in that convivial and socially-competitive atmosphere they’d each sign a purchase order for merchandise many of them couldn’t afford. Then, in a couple of weeks, the furniture would be delivered to the hostess who had contracted to pay for them. It was her responsibility to collect from the individual purchasers.

“Without trying to gain the knowledge, I became aware through overheard discussions that her net profit on each sale was in excess of 30% and also that the profit was not limited to the sale. I knew that she would sell the names and addresses of the customers to a diaper service, a baby photographer, an insurance agent, among others; and because these leads were particularly good ones, she’d receive immediate payment for each lead. I was present several times when a salesman came by and paid cash for a lead-sheet.

“In November, for my birthday, she gave me an old and valuable rosary. It was large, sterling silver, with beautiful lead-crystal beads. Her husband’s aunt had bequeathed it to her, and she wanted me to have it. I wept when she gave it to me. It was so incredibly generous. Christmas was coming and I knew she had admired a slate coffee table we had seen in a shop window, so despite its heavy price tag, I bought it for her.

“And then many of our old friends who had acted as hostesses for her began to call me to grumble about the mistreatment they were experiencing. They always prefaced their remarks by sarcastically supposing that I’d surely be interested in the kind of person my friend really was. I’d immediately derail the line of abuse, asking why they were complaining to me. Why not call her directly? I assumed they were trying to drive a wedge between her and me because they were jealous of our friendship. When they charged that she was cheap and conniving, I told them of the beautiful rosary she had given me for my birthday.

“One day I received a call from a cousin of mine who had acted as a hostess for one of these home sales’ parties. She complained bitterly about my friend’s greed and her unethical business practices. She claimed that the delivered merchandise was clearly inferior to the samples shown; and that when she complained she was reminded that there could be no returns, a policy stated on the purchase order. She also resented her collection tactics. Not only was there no grace period for payment but a threat was made to contact her husband at work or, if necessary, to take legal action. She was, my cousin said, a con artist. I recall fatuously disagreeing with this assessment of her character. ‘She’s always been honest with me,’ said I, defending her with no personal knowledge whatsoever about her business ethics. I found it ironical that my cousin further insisted that although she had recruited additional hostesses, she had not received the promised 5% commission on their sales. The conversation ended with a warning to me that I’d come to regret my blindness.

“There’s an old story about a foolish king whose uncle is planning his assassination; and a servant who has overheard the plot comes and tells the king who promptly tells his uncle about the servant’s perfidy. The uncle says, ‘Ah, the poor fellow must have lost his mind. I’ll see what I can do to help him.’ And then he has the servant killed and proceeds with the regicide. I actually considered telling my friend about this conversation, but my cousin had already called her and related my remarks; and so my friend thanked me for defending her so vigorously. I had now become the champion of her honesty.

“And then, early in December, she and her husband went away for a week to one of their regular jewelry buying trips. She asked me if, in her absence, I would accompany her brother when he made the routine furniture deliveries and collections. My help was needed because he had refused to involve himself in ‘the paperwork.’ I agreed and the following Saturday we made four deliveries. He unloaded the cartons and I collected and signed for the mostly cash remittances, sealing each group remittance in a separate envelope. The following Tuesday at cards I casually gave the four of them to her. I proudly noted that she accepted them without counting the money and, without so much as a glance, just tossed the envelopes in a drawer. This was the trust of friendship.

“A week later, she asked me not to forget to turn in the money I had collected from one of the hostesses. I was shocked. I heard that awful tone of falsity in her voice, and suddenly I felt cold with dread. My chest seemed to contract, and I could feel my heart beat against the pressure. I could hear a small voice in the distance explain that they wanted to bring the books up to date and that one account – which I distinctly knew I had paid – was still open. I heard myself protest weakly that I had indeed remitted the money, but my friend was saying, ‘Oh, no. The first three, but not the fourth. I wish I had checked when you turned in the envelopes. It’s my fault, really.’ And her husband was saying sweetly, ‘We figured maybe you had accidentally co-mingled the funds… that happens. You did have the envelopes all weekend.’ Then he added ominously, ‘But you still owe us that money.’ I looked to her brother for support, knowing that he had witnessed the transfer of money. ‘To be honest,’ he said, ‘I thought I only saw three envelopes.’

“I have an expression I use to get me through such situations. ‘This is tuition.’ My hands were so cold that I could barely hold the pen to write the check for money that I did not owe. I kept repeating to myself, ‘This is tuition. This is tuition. This is tuition.’ What the lesson was I hadn’t quite determined, but I knew it was some kind of learning experience. It was not ‘always get a receipt.’ It was a more profound lesson. I recalled that personal checks were in all four of the envelopes. The endorsement of these checks would have proven that I had, indeed, remitted the monies. But so much more was involved than money. I knew it and, what was worse, I knew that she knew it. I could hear that in the tone of her voice, too.

“But that awful night I simply invented a headache and excused myself from further card playing. I could see the smirk on her face as she walked me to the door, feigning much concern about my headache.

“I drove home like a robot, stopping when I should stop and turning when I should turn. But I wasn’t really conscious of anything. When I finally got home and was safe in my own house I tried to understand what had happened. I questioned my own version of the facts. Could I have been mistaken? I checked my car and my purse looking for the 4th envelope, knowing that I wouldn’t find it.

“For the next day or so, I was numb, stunned.

“Looking back now it’s difficult to pinpoint precisely the order of many small events that constitute a phase transition. Roughly, then, I’ll give the following order:

“Phase 1: confusion and panic. Why had my friend done this to me? What had I done to deserve such treatment? Christmas was coming and I suddenly felt desperate to retain what friends I had left and make some new ones. I made sure I sent a card to everyone who had sent me one… and to a few I had purposely left out of my original Christmas card list. I accepted an invitation to join an Arts’ discussion club, agreeing with servile gratitude to attend their next meeting in mid-January.

“I had planned to spend both a Christmas Day open house and New Year’s Eve party at my friend’s house, but now I had to make other plans. With a defiant ‘Who needs her?’ attitude, I called my brother, casually mentioning that I’d love to drop by his house Christmas Day to deliver presents to his kids… but my sister-in-law got on the phone and asked if I could come the day before or the day after.. she had planned a big dinner for her family and they didn’t know where they were going to put everyone as it was. I hung up the phone feeling as if I had been slapped.

“As cold as it was, I drove to the seashore and, along with a few other people who were equally uncommunicative, leaned on the boardwalk rail and watched the waves for hours. Then I returned to the motel and cried myself to sleep. I ate Christmas dinner in a Chinese restaurant. Then, using the holiday as an excuse, I called two old friends, trying to weasel an invitation for New Year’s Eve. I said I planned to drive about this year and pay calls on dear friends I hadn’t seen in a long time. The first one said, ‘What a pity! We’re going out of town to a party. I’d ask you to join us but it’s by invitation only.’ I said I understood. No problem. The second one I called said she was having a special New Year’s Eve dinner for some foreign houseguests. ‘There’s four of them and four of us and that makes eight and you know how it is when you’ve got flatware and dishes that are service for eight.” I said I hoped it all went well, and when I hung up I began to sob. I had been groveling.

“When I checked out of the motel, the desk clerk said something to me that startled me. He asked, ‘Were you taking a De-Sentimental Journey?’ It was a reference to the song, Sentimental Journey. ‘Gonna take a sentimental journey. Gonna set my heart at ease. Gonna make a sentimental journey to renew old memories.’ He explained that a De-Sentimental Journey accomplished the opposite; and that many people came to the seashore at Christmas just to get away from houses that were haunted by memories of someone they had loved. They didn’t want to be home for Christmas without that person. I said, ‘Maybe some of them are embarrassed to be alone on family holidays.’

“Phase 2: self-blame had begun. Driving home I began to think constructively for the first time. I had been feeling sorry for myself, not knowing whom to blame. I liked my friend and I was so sure that the feeling was mutual. But now I saw how I had allowed myself to be deceived – that I had overlooked evidence of greed because if I had acknowledged it I would have had to devalue these friends whose company contributed so much to my own self-esteem. My pride had indeed blinded me to facts that everyone else could see. Proverbs 16:18 screamed at me: ‘Pride goes before disaster; and a haughty spirit before a fall.’ Chagrined, I recalled with regret how I had spoken so smugly to people who had tried to warn me.

“Phase 3: anger. By the time I arrived home I could see that the people who had tried to warn me were not exactly concerned about me. She had harmed them, and they wanted to retaliate – through me. I felt abused, betrayed and very angry – exploited by all the parties. I fantasized about bringing them all – especially her – to justice. I’d hire a private detective if necessary to prove that I had remitted the money. I’d expose her for the fraud she was. I didn’t care what it took. So, she had sold my friendship for a few hundred dollars. Oh, I’d let her know it had been worth so very much more! I’d let them all know that I, for one, could not be treated so shabbily.

“I got over that phase fast. Fortunately my great urge to destroy the world came on a holiday weekend and all the agencies were closed. I went to bed vowing to take action at the first opportune minute; but I awakened with a more resigned attitude. I remember thinking, Why should I spend more money to prove she is a liar and a thief? To whom would I present my case? I didn’t have any more friends; and that she was a thief was precisely what the ones I used to have had been trying to tell me! All I’d accomplish was to give them a good laugh. To hell with her and the rest of them, too, I decided. Anger had turned to disgust.

“Phase 4: defeat and final humiliation. Having no alternative, I called the business associate of my friend who was to be my date for the New Year’s Eve party and left a message with his secretary expressing my regret that unavoidable circumstances had forced me to cancel. I didn’t ask for a call back, and he didn’t make one.

“For the holiday weekend, I stayed home, hiding, planning not to answer the phone. Nobody called. I invented an elaborate excuse to tell people who asked me what I had done for New Year’s Eve. Nobody asked. I went into an emotional retreat.

“The first few weeks of January were revelatory. Bereft of everything else, I turned to my Bible. As a Christian I was commanded to love my enemies and to do good to those who hated me. Impossible, I thought. How could anybody take such an order seriously? Surely, I thought, there had to be a secret message behind the commandment. It had to be a key or a metaphor. What did ‘love’ mean in this context? I brooded about it for days.

“Phase 5: dispassionate analysis. This was the big breakthrough. I began to look at myself objectively and also to see the world from my friend’s point of view. Why was she so greedy? Why had she set me up so elaborately and played with me as a cat plays with a mouse before killing it. I recalled the flattering remarks she had made and the way I proudly accepted them. What made a person need to feel so superior and so controlling? Then I remembered how stricken she had been when her father was killed. The blank expression on her face. Her mother’s grief. The blue star in the window replaced by a gold one. What had her step-father been like? She never spoke about him. Why had her brother, a grown man, come to live with her? I was no psychologist, but I could imagine troublesome situations that might have caused such behavior. It didn’t account for her husband’s behavior, but maybe he had his own story. I wasn’t trying to excuse their behavior, I was only trying to explain it. Something had caused them to be so greedy. I thought of other “white collar” criminals and how they all found such excitement in being shrewd or cunning. They delighted in outsmarting people. They seemed to be addicted to that rush of triumphant pleasure.

“I began to think about peculiar human conduct. Why did people brag about their accomplishments in order to conceal their sense of inferiority? Why did they bluster to mask timidity.

“What was friendship all about? My friend had stolen money from me. If she had asked me to give her twice the sum, I would have given it gladly. But a gift would have presented no challenge. Perhaps she needed to excel in something – as a fine actor delights in using his art to trick an audience into laughing or crying. She needed to execute a plan by which, in her mind, she would determine my happiness or misery. She could uplift me or degrade me as she chose.

“I began to see that she saw herself as being in a war or a contest. First, she divided the opposition. I had indeed severed my relationships with all our old friends. But then I asked myself, what if, at the beginning when I was still friendly with the others, she had cheated me then. Would I have brooded in silence or would I have been like the others, broadcasting my complaints about her? The ugly answer to that was that I would no doubt have joined that chorus.

“The friendship was an illusion. But why had I pursued it? She had represented quality to me; and I enhanced my own state by associating it with hers. As she was important, I became important for being near her. I examined my own history, and I suddenly realized how mechanical life was. It was all an illusion. A cause created an effect which was itself the cause of other effects. On and on it went. There was no point in blaming anyone or in praising anyone. It seemed so clear and matter-of-fact. People manipulated other people in order to satisfy their own needs. If they were afraid of being alone, they’d reach out to feel another body. If they couldn’t bear the thought of being alone in pain, they’d injure someone else. Of course there were pleasant occasions and shared joys, but I already knew the bright side. I had never considered the dark side, the shadows that give definition to light.

“And suddenly I felt as sorry for her as I had felt for myself. She was pathetic, not evil. No, I didn’t desire to call her and say, ‘All is forgiven!’ In my heart the problem simply evaporated. I truly had paid tuition, and I had completed the course. A great relief came over me, and I began to pray more seriously than I had ever prayed before. “Judge not, lest ye be judged.” There was a finality about the issue.

“In January she called me several times, and while I was polite, I simply had nothing to communicate. We chatted about the space program and politics. Once she called me from the hospital: she had had her appendix removed. I sent her a get-well card.

“Phase 6: separation. I had attended a few Arts’ club meetings, but I didn’t fit in. The members were excited about a new Ingmar Bergman film. They went in groups to see it. I went alone.

“Increasingly I found myself unable to connect properly with people. I could tell – in the club meetings and in my office – that people regarded me as standoffish one moment and pushy the next. If social interactions are a skill, I certainly had lost mine. At work I felt the most obvious change. I couldn’t, for example, join in office humor anymore. For the first time I noticed that most of the jokes demeaned people: they were racist, sexist or depended on ethnic or religious slurs for their humor; and I can’t explain why it was so, but I felt offended by the jokes. Previously I would have laughed, and if the joke seemed witty enough, I’d repeat it. But now, the jokes made me uncomfortable and sad. Soon I was left out of the joke-telling circuit. Also, I couldn’t indulge in gossip anymore. I wasn’t self-righteous. It simply hurt me to hear people mocked or whispered about. I had gossiped with the best of them before; but now I was happy to be left out of people’s conversations. In fact, I no longer cared about the opinions of others.

“In late February Lent began. I understood my religion in a new and profound way. I wanted to fear no evil. I wanted my cup to run over. I wanted to be alone with God. I began to crave solitude. I went to church every evening and felt sanctified by sacred space.

“By Easter I had become estranged from all my former friends and associates. I was still friendly whenever I saw them; but I didn’t call them; and they didn’t call me, either. I also had become impervious to disapproval. If somebody snubbed me, I shrugged it off. I didn’t make excuses for people, I simply didn’t care one way or the other whether they liked me or not. I was totally unattached to everyone. I enjoyed going alone to movies and restaurants. I browsed in bookstores and began to read the psychology of Carl Jung. I came to understand that I had integrated the Persona and both aspects of the Shadow. I was free.

“Months later I saw my friend’s brother in a line outside a movie. I looked at him as I’d look at a poster that advertised an event that had already taken place; but he was excited to see me. He got his ticket first and came back to talk. His sister and he were no longer on speaking terms, he said, and then he apologized for ‘getting involved’ in her scheme to con me out of the money. I said, ‘I understand. She’s your sister, after all.’ He laughed sardonically. ‘Blood doesn’t mean anything to her. She’s been a liar and a cheat all her life. She just screwed me out of my half of an investment we made.’ I shrugged and said, ‘I guess she needed the money.’ My unwillingness to side with him chafed him. ‘You know,’ he said with malignant satisfaction, ‘that rosary she gave you – she stole it from one of the hostesses.’ Then he walked away. The next day I delivered the rosary to the Bishop’s office.

“A year later I met my husband in a bookstore. Our marriage was truly sacramental. We moved to another town and, with determination but without rancor, I distanced myself from my family. I could not get involved in their lives. I found no joy in their joys and no quarrel with their quarrels. I had heard that my friend had also moved away, but I did not know where.

“We had two children and raised them happily and successfully. My husband was ten years older than I; and when he died, I entered the convent – on the twenty-fifth anniversary of our wedding day. But all through the years I took care of my own family, I always reserved time each day for meditation and Bible study. In the convent, I finally achieved the mystical goal.

“When I look back I remember how hurt I had been by my friend. Now I shall be eternally grateful to her.”

This lady, on her own and without a human teacher or a laboratory, entered the Bridal Chamber and delivered the Child. Curiously, it was not customary for nuns to discuss visions and certain other spiritual experiences in the convent; and so she often confided them to me. The only difficult period of her life I knew about occurred early in her noviate when, after having been a mother of children, she suddenly found herself a child’s child. Most of the nuns who were her immediate superiors were young and inexperienced.

Requiring no esoteric texts, she had relied on her own intuitive powers, her willingness to adhere to her religion’s principles, and her Bible’s comfort and guidance to solve her own samsaric problems. She remained devoted to Christ (who safely held her ‘Hero’ projection) and, as we would remain devoted to the Buddha (those of us who don’t go around ‘spitting in his face,’ that is), never required any adjustment or severance of this bond.

Clearly, it was due to having already integrated her Shadow and Persona that she was able to enjoy domestic life so completely.

The difference between integration and simple withdrawal is the need to re-project the archetype. An integrated archetype is restored to the psyche as a permanent resident, manifesting itself in visions.

By the nature and content of these visions, a spiritual alchemist would easily be able to calibrate his progress.

Part 3 to follow, discusses the phases of the regimen

Author: Ming Zhen Shakya

Image credit: Michael Veard

A Single Thread is not a blog. If for some reason you need elucidation on the teaching, please contact the editor at: yao.xiang.editor@gmail.com