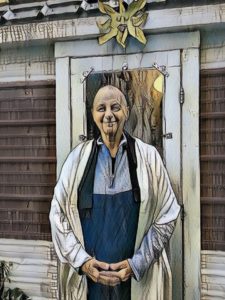

Earlier this summer, I took vows to live my life as a Zen monk. In a dawn ritual, my head was shaved, I received a hand-sewn robe and a new name, Old Fire Skyward. I was welcomed by the Buddha and by my teacher into the Contemplative Order of Hsu Yun.

Earlier this summer, I took vows to live my life as a Zen monk. In a dawn ritual, my head was shaved, I received a hand-sewn robe and a new name, Old Fire Skyward. I was welcomed by the Buddha and by my teacher into the Contemplative Order of Hsu Yun.

The following day, a five-hour drive back to southwestern Wisconsin, a region of small towns, deep river valleys and high ridges with views of family farms and woodlands stretching to the far horizon. Three miles from town on a ridge-top meadow where I live with my husband B. and our dog, I began a new cycle of spiritual unfolding, nourished and guided by vows and name, robe and haircut.

Several weeks later I read a beautiful essay, “A Plumb Line for Our Lives,” in which John Backman asks, “Am I doing it right?” Reading his thoughtful reflection was a revelation. It seems there are others in addition to me who ask this question of themselves as they travel the path of solitude, silence and spiritual seeking. Backman’s question reminds me of the child’s game of hide and seek. The “seeker” searches for where the hidden players might be. I remember the thrill of the search, the possibility of discovery around every corner, in every closet, and the frustration and doubt that set in as the minutes ticked by and my seeking was still in vain. It helped to have a witness who could say to me, “You’re getting warm! Really warm!” With the reassurance offered by this witness, I could carry on my seeking, knowing that I was on track toward uncovering that which was hidden.

Seeking the Divine can be similar. Sometimes there is doubt, sometimes I want to know that I am getting warm. For the likes of early Christian monastics, the boundaries that established the Path of the seeker were solid and uncompromising: three windows, open at precise times. A modern version of monasticism, the one in which I have been trained, is that of the householder monastic. Living life as an ordinary person, I do the dishes and feed the dog, weed the gardens and build a rain water collection system, go for groceries, help neighbors harvest the garlic.

A Zen monk lives her ordinary life as a spiritual practice, each task and each encounter an opportunity to listen, to see, to pay full attention, to seek what is hidden in plain sight, in everything that arises. In this context, the witness, the clarity of one’s seeking rests within the structure provided by the ever-changing present. Fully giving oneself over to this place and this moment, without any coming or going and with full acceptance of all that is coming and going: This is the Way, this is, “You are getting warmer.”

The here and now of my life takes place in a re-purposed travel-trailer. This tiny dwelling-place is off the grid, running on solar electric power (fridge and lights and electronic devices), propane (cookstove and heater) wood (stove for second heat source) and plenty of human muscle. We haul water in 3-gallon jugs and a pull-cart across the ridge-top on a grassy path from the well. Groceries and dog food, bird seed and propane tanks are hauled in too. Garbage and laundry are hauled out, gray water is hoisted onto plantings, humanure and kitchen waste are carried down the hill to an enclosed composting bin.

Cellular data affords easy internet and phone connectivity; hence we are well-connected to the secular world while and also retreated from it. Far from streetlights and highways and the imperative to lock our doors, we live within the cycles the sun and moon and stars and seasons make. We are reminded of where we are by the bird migrations, the oak saplings, the young fruit trees and the flowers seeded in June, all growing toward their maturity, the skeletons of old trees falling, then cut up for firewood. We endure bugs and their biting, wind and terrible storms, heat and humidity, cold and mud so that we can be a part of life on this ridge-top, so that it can shepherd us through the bitter sweetness of everything changing, everything.

Six hundred feet to the southwest dwell our closest neighbors and dear friends, M & E, who own these twenty-seven acres. In their cozy compound can be found more amenities of daily life including a shower, a freezer, an air conditioner, jam-making, problem-solving, shared dinners. Around their house are abundant tree lines to break the wind and sun, flower and vegetable gardens, berry bushes and fruit trees from generations of farmers and gardeners who have called this land home.

This is my window into the larger world: our house on the meadow and off the grid, the larger farm and the community of people and pets who live here. The next ring expanding out includes the grocery and hardware stores and all the other stimulations of town, my large extended family, a half-hour’s drive away including aging parents and an assortment of siblings, cousins, their offspring and their aging parents.

Every day, whatever else is happening out the door, down the driveway and on the device screens that beckon us into the material world, B & I follow a routine of meditation, spiritual study and writing, silence and solitude. We set up an altar each morning at the table that also serves as our dining table and desk. Candle and incense, chimes and bells come off the shelves to take center stage with the flowers and the statue of the Buddha that live permanently at the heart of our tiny abode.

I go back and forth between early mornings at the altar, seeking the Absolute purity of timeless awareness, then breakfast, followed by time to write and reflect. A mid-day work period can find me weeding, hauling, building, repairing, driving to town with a list. After lunch and rest, another period of solitude and silence or study before the evening meal. Here on the high meadow, using the events around me and within me as fuel for the proverbial old fire within, I seek the light of wisdom, rising skyward.

I sit in the middle of the fear I felt when a torrential two-day storm caught me alone on the farm with just my dog for company. I grapple with my tendency to make every aspect of life part of my drive toward accomplishment, whether tending gardens or making a meal. I struggle to share this life with B, the constant navigation of small spaces, the compromises, the carving out of solitude and silence in two hundred and forty square feet. I watch all the ways my body, now well into its sixth decade, is diminishing in its capacity to perform the physical tasks required of life here.

From this fluid flow of absolute and particular, I search within the pain, fear and difficulty of my life for what lies hidden there. I practice opening to the suffering as an offering, pointing me toward the delusion that this body and mind are who I am. There is great spiritual power in Just This, this here and now, unencumbered by the self-motivated habits and misunderstandings of a lifetime.

Within the cycle of delusion and suffering leading towards insight and nourishment are those moments when I lose my confidence in the process of this unfolding. Insight seems unreachable. Certainly (it feels) I am getting colder, not warmer. I forget to trust the seeking without finding. I forget the profound simplicity of “stay right here.” Behind my question, “Am I doing it right?” is the precarious perch I balance on, the human form I inhabit and the spiritual being I am in a groundless dance, no place to land except Here.

Powerlessness, the turning away from drive and toward open receptivity, the trust that IT is everywhere around me, this quality of light is new to my eyes. While I need to orient towards renunciation, instead, my usual bend is towards sturdy self-reliance, that pioneer quality of dependence solely upon my own faculties, my agency and my purposeful seeking. Herein lies another source of my questioning, “Am I doing it right?” On the ridge, I can see when my work bears fruit, and when I cannot see, I have the work itself to sustain me. My pioneering self is not familiar with waiting, alone, without a sign, in the open stillness.

My teacher and guide on this path, when I ask her, “Am I getting warm?” she says, “Relax.” Without thinking, without measuring, she says, just meet what comes and relax. So, as the summer winds down and all the multitude of life that has been growing, pushing upward around me responds to the diminishing light by sending out its final fruits, I turn my focus toward slowing down, calming down, relaxing the push. The grasses dry and bend, the apples drop from the trees, the milkweed and butterfly weed wear fat pods full of seeds and bright red berries adorn the fence rows. I look as if seeing with new eyes.

I see myself reflected in a mirror or window and I know that my vows and my new appearance are telling me of a ripening at the core of my being. That which I seek lives within me. The shaved head declares this truth, previously hidden even from myself, like the seeds in a still-closed pod. My seed-pod monk-hood now displays its wealth of fertility. I have come out of the Buddhist closet.

“I Am an Ordained Buddhist Monk.”

My now-visible status is an offering to my own seeking spirit: I have been welcomed into the Way. I have been embraced and I am being guided.

There will be groundlessness, it will get dark. And within every cycle there are the fruits that ripen to feed my hunger. In the wealth of the autumn, here I am. With gratitude for the harvest, and for the seeking.

Author: Lao Huo Shakya

ZATMA is not a blog. If for some reason you need elucidation on the teaching, please contact the editor at: yao.xiang.editor@gmail.com