The Anna Karenina Principle, “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way,” may be used by scientists to explain why so few animals have lent themselves to domestication, but Tolstoy’s observation, upon which the principle is based, is a bit suspect. It suggests that he found a statistically relevant number of happy families to include in his study.

Our experience would lead us to believe that the number of happy families is somewhat more rare than the extraordinarily small number of wild animals that have allowed themselves to live amongst us in a manageable way. Perhaps the families Tolstoy considered happy might actually have been in their nascent phase of a unique misery. Ultimately it may all depend upon what passed for happiness in 19th Century Russia.

Myla Goldberg, in her splendid novel, Bee Season, examines a uniquely unhappy family. Her study is of interest to us since it is religion that is the catalyst that hastens the decomposition of what was presumed to be a stable family unit.

Like a Wagnerian leitmotif that heralds a significant presence, the theme of Jewish mysticism occurs throughout her book. To whatever extent Goldberg stays within this thematic limit, she is on our turf. She chooses as her subjects a middle class Jewish family living in suburban Philadelphia in roughly 1988. What makes her tale remarkable is the ego-centered way that Saul Naumann, the “patriarch” of that family, pursues, through the Kabbalah’s vaunted writings, mystical knowledge of God. A Jew does not utter the name of God lightly, yet, with the zeal of a social-climber, Saul desires to gain that kind of aristocratic intimacy, that “first name” casual ease, with which a mystic interacts with divinity. Though he admittedly has never had a mystical experience, and worse, has denigrated God’s theophanic prerogatives to the level of a man’s simple decision to ingest an LSD tab, he regards himself as completely qualified to teach the subject. This is hubris, a sin that in the list of punishable offenses is in a class by itself – and at the awful top of the page.

The Kabbalah master who interests him most is Abraham Abulafia, a spanish mystic of the 13th Century. To Abulafia, since all creation was ordained by the divine pronunciation of “the Word,” it followed that words, when carefully approached through the permutations of consonants and vowels, contained a direct route back to their divine source. Appellations are particularly significant, the belief being that knowing the name of any entity gives power to the one who knows and utters it. The ultimate quest, therefore, is to gain the right to utter the name of God. At the outset, Abulafia and mystics of every religion require that one who undertakes the sacred discipline has purified himself of even the slightest material-world taint and also that he love God unreservedly. Saul, in his destructive self-absorption, is clueless. He does not realize that he is the very embodiment of the world he desperately wants to be able to say he has transcended.

A look at Saul’s personal history reveals a somewhat less than heroic individual. His father, an auto mechanic, in response to his own father’s rejection of his wife because she was not “sufficiently Jewish,” had renounced Judaism and anglicized the family name to Newman. Saul, unwilling to follow his father into either car repairing or renunciation, revived his orthodox heritage, restored his Naumann name, and entered college where, owing to his proficiency in the use and distribution of LSD and his boasts of traversing several heavens in LSD’s yana, he gained celebrity status on campus; the sexual favors of coeds; spending money, a bachelor’s degree; and draft exemption from military service in Viet Nam. It was the last of these acquisitions that his father found unacceptable, and he dissociated himself from his “hippy” son.

Saul, convinced that his acid trips are mystical adventures indicative of clerical destiny, prepares himself for the rabbinate. In addition to his other courses, he studies Hebrew, attends synagogue services, and dedicates himself to deciphering the Kabbalah’s esoteric writings. Being such a promising candidate, he is awarded a scholarship to Rabbinical school; but being Saul, he cannot see ahead to any deleterious consequences his willfulness might have. He talks a classmate into trying LSD, an experiment that goes sadly awry, and he is promptly expelled from the school.

Impoverished, he returns to his old campus where his fame as a psychedelic guide induces students to let him sleep on a dirty mattress in the burned out attic of their house. The room is not insulated and has no electrical outlets or other amenities. Yet, he manages, spending his days in the library, independently studying Hebrew, Judaism and the Kabbalah. Disabused finally of the notion that LSD can effect an introduction to divinity and lacking the appropriate setting for assignations, he is not inclined to waste time in fruitless pursuits. He marries an emotionally fragile but highly intellectual Jewish lawyer who has recently been orphaned and possesses an inherited income.

Their attraction is mutual. Saul’s bride, Miriam, has social theories that are in need of “wife and mother” experience. She has never had a serious romantic relationship and regards it as especially fortuitous that the man who wants to win her can, in intimate moments, whisper the sweet secrets of Judaic theology to her. It also helps that he aspires to be a respectable Jewish cleric – a cantor – who will have sufficient free time to be a househusband. She will need this domestic support if she is to pursue her career in estate law and other in camera activities. Saul much appreciates her intellectualism and professional status and, of course, the financial security which will allow him to do what she needs and he wants, i.e., to study, stay home, and do as little work as possible while remaining respectable.

His union with Miriam produces for Saul a comfortable home; a private study in which he can peruse mystical texts; honorific but light employment at a local synagogue as a cantor and occasional teacher of Judaism, and a son, Aaron, who is labeled “talented and gifted” by his teachers. Having no complaints about his life, Saul easily maintains a congenial persona. He is a househusband who cooks but does not do the dishes. It is Miriam who comes home from work to eat and then scour the pots and pans and, in her clearly obsessive way, to clean. Saul eats and immediately repairs to his study while Miriam fanatically wipes and scrubs. She sleeps for only a few hours a night, a lack of rest which Saul regards as admirable. He calculates that she gains two and a half months more wakeful hours a year than the average person. It does not occur to him that a constant lack of sleep may be harmful to her health.

Six years after Aaron’s birth, Saul and Miriam have a daughter, Eliza, who, to Saul’s unconcealed disappointment, is not considered “talented and gifted” by her teachers. She receives A’s in spelling, but is otherwise an ordinary, lackluster student.

Like his father, Aaron has had an experience that he mistakenly believes is mystical. When he is eight years old, during a nighttime flight, he sees in the darkened haze outside the window, a mysterious red glow, blinking as if giving a message in divine morse code. He doesn’t realize that it is one of the plane’s running lights. But the would-be epiphany’s image persists, beckoning him towards a religious vocation.

Aaron has no friends. He comes home from school and watches television or plays games with his little sister. At school he is the victim of cruel tricks and vicious beatings by bullies. After one particularly brutal attack, Saul is asked to bring a change of clothing to the school. He asks his son to name his attackers, but Aaron will reply only that he has fallen; and Saul, secretly pleased that his son is no stoolpigeon, declines to press him for the truth. Instead, he privately proposes that the two of them become a scholarly team, and he rewards the boy by allowing him to come into his private study to learn guitar, Judaism, and Hebrew. It is an invitation to someone who has lived in cold comfort to come and sit by the fire and get warm. A belief in intellectual superiority and a father’s attention will be Aaron’s compensation for suffering through a few more years of bruises and the constant fear of thugs. Saul, supremely confident that he has chosen the civilized way to deal with the crisis, will not suspect that in the most cowardly fashion he has failed to protect his child.

Eliza has no friends, either. But now that Aaron has been admitted to their father’s study, she must watch TV alone and sadly listen to the happy sounds of music and laughter that seep through air vents and from beneath the study’s closed door. When Bee Season opens, Eliza is ten years old, and she still has never set foot inside the sacred room. One startling day, she competes in her school’s spelling bee and wins. She is given a letter to give to her parents, informing them of her victory and qualification to compete in the district competition. She loves her parents and is eager to receive their approbation; but her mother, as usual, is absent; and her father, as usual, is ensconced in his study. She stands before the closed door too fearful of breaking the rules to knock. Finally, she timorously pushes the letter under the door; but days pass without Saul acknowledging its receipt. Suspecting that he is unimpressed by this “too little, too late” accomplishment, she asks her brother to drive her to the contest.

Saul is so self-absorbed that he does not notice that for the last ten years of his marriage to Miriam, she has only been pretending to go to her law office every day. The “paycheck” with which she supports him and the children is taken from the money she inherited. Worse, Miriam is a kleptomaniac. Ever since she was an obsessive, over-indulged child she has been stealing things. After she gave birth to Eliza she ceased practicing law. Yet, with Saul staying at home, she dresses for work every morning and waves goodbye; but her destination is not a law office. She goes to reconnoiter department stores and the homes of strangers to locate and appropriate peculiar things that convey to her secret messages of fulfillment. During each foray she seeks a missing piece that will fit into a mysteriously ordained arrangement that she calls “Perfectamundo.” She lives with the constant need to acquire by stealth an item she will know only when it conveys its nature to her: a pen, a dish, a ball – a trifle that somehow is commandingly significant. She could not explain this need to herself until, during Saul’s courtship, he related to her the doctrine of Tikkun Olam. According to this explanation, God placed part of himself into sacred vessels of light when he created the world. These vessels, unable to contain God’s glory, shattered into spark-filled shards that are hidden in the material world; and man’s task is to gather these shards and repair the vessel. This has been her Quest, she decides, her true motive. From thousands of items, only one may reveal its divine content; but recognizing it, she must take the precious item and fit it into an artistic design – one of many creations she meticulously maintains in a rented storage facility. This is what she has been doing five days a week for ten years.

It is a measure of Saul’s ego-centricity that he is ignorant of the circumstances of his wife’s life. It has never occurred to him to suspect that it is odd that at least for the last ten years he has not met or even spoken to another attorney or employee from her law firm; or that although he gets the mail every day he has never seen any official mail regarding a license renewal or any other business communication; or that he never sees her with legal documents or hears her speak to a client on the phone; or that never, when he telephones her ‘at work’ does she answer the phone but that always he has had to leave a recorded message; or that never when attending a business, shopping, social, or religious event with her has he encountered a secretary, a client, or anybody who did anything whatsoever that would indicate that she had a professional life; or that he has somehow overlooked the lines in their income tax statement that give quite specific information about sources of income. He doesn’t know about Miriam’s life because it does not disrupt his own. When it does impinge upon it, as, for example, towards the end of the ten year period when she is emotionally disintegrating and nightly reaches out to him sexually in the frantic hope that this connection will save her from psychological annihilation, he backs away from her. After having rejected her “six times out of ten”‘ he is exasperated and responds rapaciously, leaving her bloodied. This uncharacteristic brutality gives him a noble reason to start sleeping in his study. Like Larry Talbot at full moon, he keeps the door locked to protect the innocent from his wolfishness. Miriam, needing him, has tried and failed to open the door.

Eliza has lived as an accidental guest in her house. Her food, clothing and shelter are provided; but it is of no particular concern to her hosts whether or not she is happy. Not until she returns home from the district spelling bee with the winner’s trophy – the evidence of her proficiency with words – does her father begin to appreciate her existence. He is intrigued by this unwonted excellence and encouraged by the way she goes to her room every night to practice for the area finals in Philadelphia. Proudly he announces that the entire family will attend the contest.

It is there in Philadelphia that Saul is stunned to witness Eliza’s spelling technique. She closes her eyes, enters a meditative trance, and slowly pronounces the correct order of letters. He knows to a certainty that he has spawned a mystical prodigy. She wins the area contest and will compete in the national finals. Saul plans the strategy and tactics by which he will lead her to win much more.

Eliza happily shares the details of her mysterious technique. “I start out hearing the word in my head in the voice of whoever said it to me,” she explains. “Then the voice changes into something that’s not their voice or my voice. And I know when that happens it’s the word’s voice, that the word is talking to me…. I keep my eyes closed so that I can see the word in my head. When I start hearing the word’s voice, the letters start arranging themselves. Sometimes it takes awhile for them to look right, but when they do, they stop moving and I know that that’s the right spelling.. So then I just say what I’m seeing and that’s it.” She will later describe the process as having her head become a kind of movie theater with a silver screen on which the letters write themselves. Eight hundred years earlier, Abraham Abulafia said that the advanced disciple should, “let the word’s letters form as if upon a bright mirror,” which is precisely what Eliza is already able to do.

Clearly, her mind has moved through the portals of transcendence. “The word speaking the word” is God speaking the word, opening up the letters, as Abulafia had said, to describe the origin of all creation.

But Saul, who has never even meditated successfully, will now presume to become the spiritual master of one through whom God already speaks. Summarily, Saul disbands his “team” with Aaron, evicting the boy from the sacred study’s warmth. Saul will help Eliza to prepare for the national spelling bee and while he is ostensibly doing that, he will plant Abulafian seeds in her mind. (It is a commonplace in religion. Self-aggrandizing incompetents often presume to mentor humble adepts.)

Aaron, understanding none of this, is left to question the worth of the religion he has been taught. (This too, is a commonplace. Especially when a child’s social life is invested in his religious life and that life is parent-dependent, disillusionment with a parent invariably extends to the religion.) Aaron explores other faiths; and one day meets a sympathetic, unassuming young man who invites him to attend a Hari Krishna meeting. Aaron visits the ashram, and finds, in the group’s conviviality and joyful abandon, that he now possesses friends. He also meets a girl who inspires his romantic interest.

Although she uncomfortably senses that his agenda is not exactly hers, Eliza enjoys spending all of her free time with her father, preparing for the nationals. Saul persists in introducing spelling words that have a religious connotation and insisting on drawing her into a discussion of the word. Although he can see that she is becoming increasingly distressed by this tangential discipline, he cannot resist exercising his pedantic control.

Only Saul and Eliza go to Washington, D.C. Despite her natural apprehensions about competing in the nationals, he will not alter his agenda and tests her with the German word “gegenschein” (the sun’s glowing reflection in the opposite side of the sky) and counters her reluctance with pointed Abulafian instructions on how she should mystically create the word in her mind. Her confusion and self-doubt inevitably result. She does not win the competition.

The defeat matters little to Saul. He can now begin Eliza’s mystical instructions in ernest. He glowingly speaks of the ecstasies of Shefa, direct communication with God, prodding her interest by flattering assurances that she will succeed where he, after twenty years of trying, has failed. He teases the ten year girl with Abulafia’s admonitions to proceed slowly because of the power that can be unleashed. Opening one of Abulafia’s texts, he asks Eliza to read:

Make yourself right. Meditate in a special place. Cleanse your heart and soul of all other thoughts in the world, then begin to permute a number of letters. Permute the letters, back and forth, and in this manner, you will reach the first level.. As a result of your concentration on the letters, your mind will become bound to them. From these permutations, you will gain new knowledge that you never learned from human traditions nor derived from intellectual analysis. It will arouse in you many words, one after the other.

And these words, Goldberg notes, “which before had seemed as distant and dead as Abulafia himself, are suddenly affixed in her head as if born there and not across an ocean centuries before. ‘That’s exactly what it’s like,’ Eliza whispers, amazed someone could describe so well an experience she thought was hers alone.”

Saul skips ahead until he comes to a special passage which he asks her to read aloud:

You will feel then as if an additional spirit is within you, arousing you and strengthening you, passing through your entire body and giving you pleasure. You will experience ecstasy and trembling. There will be no question that, through this wondrous method, you have reached one of the Fifty Gates of Understanding. This is the lowest gate.

“That, ” says Saul, “is what we’re aiming for.” His ignorance is such that he does not realize that the instruction includes an experience of samadhi, the orgasmic ecstasy of divine union – which is hardly an experience to encourage a child to pursue. He intensifies her training sessions, intimating that if she strives she will eventually be permitted to read a book that contains the instructions for speaking directly to God. He shows her the book and where he has placed it on the shelf.

Saul begins Abulafia’s mystical regimen by asking Eliza to “permute” small English words. Assuming that no letter is duplicated, the number of possible letter combinations is determined by the factorial of the total number of letters. A three letter word (3!) can be written 3 x 2 x 1 = 6 ways.

bad, bda, adb, abd, dba, dab.

A four letter word can be written 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = 24 ways.

FOUR, FORU, FURO, FUOR, FROU, FRUO

OURF, OUFR, ORFU, ORUF, OFUR, OFRU

URFO, UROF, UFOR, UFRO, UORF, UOFR

RFOU, RFUO, ROUF, ROFU, RUFO, RUOF

If spelled vertically, all the letters in the word “four” are represented.

Naturally a five letter word has 5! combinations; 5 x 4 x 3 x 2 x 1 = 120. Eliza is no slouch. She gets into the rhythm of permutation and quickly tackles 6! words such as ‘mantle,’ filling ten pages to write all 720 possible letter combinations.

She is ready to move up to the next level, the recitation of vowel mantras. Exactly as a guru would recite “Ommmm” she intones “Aaaaaaaa,” slowly turning her head. Saul is astonished as she continues to chant the mantra to transcendental perfection, instinctively moving her head in the manner that he knows Abulafia had instructed. Later, her childish ambition overriding the admonition against attempting more advanced methods, she waits until an afternoon that her father is teaching in the synagogue and takes down Abulafia’s text. She begins to practice, chanting the sacred vowels, breathing and turning in accordance with the prescribed movements.

As the text describes, but independently of any consonant, she would straightforwardly face east, inhale, and chant a protracted Ooooooo (cholem, “o” as in “so”) in one long breath as she raises her face upwards. She would prostrate herself, rise, and inhale with face forward. Then she would slowly chant Eeeeeee (chirek “e” as in “see”) as she lowered her face. Again she would prostrate herself. She would rise, inhale, and keeping her face forward throughout, she would chant Uuuuuuu (shuruk “u” as in “true”). She would prostrate herself, rise, and with face forward, inhale, and slowly turn her head to the right as she chants Iiiiiiiiii (tsere “i” as in “high”). She would prostrate herself, rise, and with face forward, inhale, and slowly turn her head to the left as she chants Aaaaaaaa (kamatz “a” as in father).

Aaron has been spending as many evenings and weekends as possible at the Krishna ashram. Saul regards the boy’s interest in other religions as an ephemeral situation; but Aaron fully intends to move into the ashram, a defection that he knows – but no longer cares – will distress his father. Miriam, too, is spending more time away from home, she has, at times, come home injured and disheveled. Saul has been paying little attention to anyone but his prized pupil. The new school term’s spelling bee is on the horizon.

The crisis arrives. Miriam has been arrested and is being held in a mental hospital. She was apprehended in a private home while trying to steal a vase. Saul goes to the police station where an officer takes him to the large public storage shed that Miriam had first given as her home address. He is confronted by a sickening array of fantastically arranged objects: buttons, shoes, glassware, years worth of accumulated thefts.

Saul, trying to account for their mother’s absense, tells the children that she has temporarily been admitted to a mental hospital and that the police were involved because their mother’s illness involved stealing things. Aaron and Eliza. knowing that their father has been sleeping in his study, do not believe this.

When Aaron insists upon proof and takes an accusatory attitude towards his father, Saul reacts with a viciousness that belies his congenial persona. “If you want proof, just look at yourself. Like mother, like son. For the past few weeks you’ve been going around in an orange robe telling me about heavenly planets and rebirth and sniffing the hand you use for your prayer beads like it had been touching a woman, not that you know what that would smell like. Why can’t you just be like me, Aaron? When I was your age, I had friends. Real friends, not religious freaks who only saw me as one more body to sell flowers in an airport–” Eliza begins to scream.

Saul’s emphasis upon “that” is a not too subtle accusation of homosexuality – he has resented Aaron’s friendship with the young man from the ashram. The hostility between Saul and his father is reenacted now between Saul and his son. Saul will know how long that hostility can last. The only time Aaron ever saw his grandfather was when the old man was in his coffin and Saul brought him along when making the obligatory funeral call.

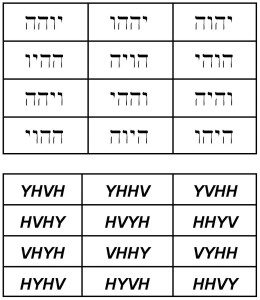

Eliza, motivated now by a desire to communicate with God so that she can ask Him to correct all that has gone awry, takes down the forbidden book, and moves up to the next level. She practices permuting a name with the vowels. YHVH, for example, would have twelve combinations.

YHVH, YVHH, YHHV

HVHY, HHVY, HYHV

VYHH, VHHY, VHYH

HHYV, HYVH, HVYH

She then combines the consonants yod, vav, and heh (YVH) with the five vowels (a,e,i,o,u) and in all possible ways, permutes them. Finished the printing, she chants them rhythmically.

Eliza is disappointed in all of the results because she has neither seen any person appear nor heard the thunderous voice of God, and she therefore feels unqualified to begin the ultimate permutation, the sacred “Name of Seventy-Two.” Then, as she reads through Abulafia’s text she fixes on a word she had overlooked: the voice may also speak to her softly! “loud or soft.” She has often heard the soft voice! She is, after all, qualified!

The Seventy-Two names are derived from Exodus; Chapter 14, Verses 19-21:

19. And the angel of God, which went before the camp of Israel, removed and went behind them; and the pillar of the cloud went from before their face, and stood behind them:

וַיָּבֹאבֵּין׀מַחֲנֵהמִצְרַיִםוּבֵיןמַחֲנֵהיִשְׂרָאֵלוַיְהִיהֶעָנָןוְהַחֹשֶׁךְוַיָּאֶראֶת־הַלָּיְלָהוְלֹא־קָרַבזֶהאֶל־זֶהכָּל־הַלָּיְלָה׃

20. And it came between the camp of the Egyptians and the camp of Israel; and it was a cloud and darkness, but it gave light by night: so that the one came not near the other all the night.

וַיֵּטמֹשֶׁהאֶת־יָדֹועַל־הַיָּםוַיֹּולֶךְיְהוָה׀אֶת־הַיָּםבְּרוּחַקָדִיםעַזָּהכָּל־הַלַּיְלָהוַיָּשֶׂםאֶת־הַיָּםלֶחָרָבָהוַיִּבָּקְעוּהַמָּיִם׃

21. And Moses stretched out his hand over the sea; and the LORD caused the sea to go by a strong east wind all that night, and made the sea dry, and the waters were divided.

A complex formula is applied by which the first letter of the first line (Hebrew is read from right to left and, at least in this case, “as the ox ploughs” (boustrophphedon) which means that at the end of the first line the eye drops directly down to the word beneath it and that line is read left to right and at the end of that line the eye drops down to begin the third line right to left. Therefore, to form a triplet, the first letter of the first line would be grouped with the last letter of the second line and the first letter of the third line, or, more simply, the triplets are formed by reading straight down.. Each line has seventy two letters, therefore there are 72 triplets. These are traditionally arranged:

With the recklessness of a sorcerer’s apprentice, Eliza now begins to chant the sacred Seventy-Two names. As she pronounces the final name she falls into a convulsive trance.

It is difficult to convey the fact that the religious life and the mystical life have little in common. They are not merely the infrared and ultraviolet of a visible spiritual spectrum.

Religion is taught. It is external and is confined to the material world’s skandhas to which the conscious mind belongs. A man studies his religion, prays, conforms his behavior as best he can to its precepts, and participates in its liturgical life, weaving his social and domestic life into its calendar. And all of this is consciously done. He may believe in his religion’s worth sufficiently to martyr himself in its cause; but this does not make him a mystic.

Mysticism is genetically encoded, It is not a mutant gene. Everyman who possesses a central nervous system has inherited the potential for experiencing divinity within himself providing he can transcend his ego-conscious mind. In the mystical realm there is no difference between a priest, guru, shaman, zen master, rabbi, imam, or an ordinary person who is unheralded in religion’s courts. Again, In the state of transcendence there are no distinctions between persons, religions, or, the strangely limited varieties of transcendental experience – as centuries worth of artwork and narratives have attested.

Religions, at their base level, i.e., the level at which families form congregations, are not only different from each other, they are intolerant of each other. Contempt usually characterizes their mutual regard. Each religion claims sole authority, chosen status, and the exclusive right to know and interpret divine will. Wars can be fought over a line of scripture.

Fortunately, each religion has a mystical ladder; and mystics are simply those persons who have ascended the various ladders. As they stand at the top rung they can see each other clearly, and they cannot detect a single difference amongst themselves. They often read, reverentially and with pleasure, each other’s scriptures, poetry, and prayers.

The indispensable core experience which defines mysticism is the direct communication with God, regardless of the name given God – Buddha Self, Atman, Jehova – or whether or not God is perceived as a Trinity of Persons, or even whether the mystic’s religious affiliation considers God an external creator or an internal force.

The mystical process is initiated by the integration of the two Shadow archetypes: the friend and the enemy aspects of the Herd Instinct. It is for this reason that a degree of withdrawal from society usually accompanies this initial integration experience. The mystic no longer has those sophomoric love-hate interests in family affairs, political figures or current events. The integrated “Friend” often appears to him in archetypal dreams or in meditations. Carl Jung would hold conversations with his “Friend” whom he called Philemon.

Skill in concentration and meditation lead into Tattva #4, Samadhi, the ecstasy of divine union. But the great mystical events require that the Buddha Self extinguish the ego, if only briefly, and make Its presence known. This marvelous event is called satori, Tattva #3, a Trinitarian experience. Before the next great event, the mysterium coniunctionis, can occur, the Anima or Animus must be integrated so that it can subsume the mystic’s ego-identity while he or she is in the meditative state. Several of the principal archetypes will subsequently complete the integration and subsumation process.

Eliza’s motives for entering sacred space are benign. Abulafia’s methods may have given her several new techniques, but the technique does not produce the result, it only facilitates it. Eliza already had reached mystical heights in meditation: a Trinitarian suppression of her ego and a pristine visionary experience. Abulafia allowed her to recognize that they were “what is known as” mystical experiences. Although other mystical disciplines would have served as well, he used one that we immediately recognize in the chakra system. A look at Sir John Woodroffe’s The Serpent Power reveals the same technique of burdening the ego with remembering a dazzling array of details about each of the chakras: colors, number of petals, letters of the alphabet inscribed on the petals rhythmically recited, bija mantra, musical note, animal, geometric shapes, god and goddess and each of the numerous objects held in their hands, the functions over which the chakra presides, and so on. By burdening consciousness with so many details to focus upon, there is no space into which ego-consciousness can insert itself. Alchemy accomplishes the identical feat by forcing the practitioner to employ a variety of arcane disciplines – metals, gods, astronomy, astrology, chemical changes, instruments, and the most cryptic references to spiritual states that have ever been recorded.

Slow chanting with interspersed prostration is frequently done in Chinese Chan temples. Ah-mi-to-fu is the way that Amitabha’s name is pronounced; and often, hours are spent chanting the name and then prostrating oneself. Up and down. Up and down.

Visualizing each letter as upon a mirror or as suspended in space, radiant in its absolute perfection, is a standard Platonic Ideal Form meditative experience.

Seeing the image of a divine person who may be questioned is known in Daoism as a successful result of the Egress Meditation on the Immortal Foetus, or in Buddhism as producing the Diamond Body. In alchemy, Abulafia’s method is known by a variety of names all having to do with the Hermetic production of the Solar or Royal King.

Attaining a peculiar radiance, if only for a few days, is known tomystics in all religions.

Myla Goldberg has indeed created a family with a unique misery. Saul Naumann is neither Tartuffe nor Torquemada. He’s not a womanizer and he doesn’t beat his wife or children. His failures as husband, father, son, and teacher have all been caused by his overwhelming self-absorption. He presents himself as an affable fellow, a respectable Man of the Cloth and Judaic scholar, liberal in his views, tolerant, devout, and attentive to the needs of his family and congregation. He us none of these things. He is merely the type person with whom all religions at their base level are cursed: the egotist who is so obsessed with acquiring spiritual power that he will sacrifice the lives, property, and happiness of all who come under his control.