The five act opera, L’Amour de Loin (Love from Afar) composed by Kaija Saariaho, received its world premiere performance in 2000 at the Salzburg Festival. I saw it as part of the Metropolitan Opera Live in HD series in December 2016. In what follows, everything presented in quotations, except when noted otherwise, is from the French-language libretto written by Amin Maalouf and translated by George Hall.

“We know a thing only by uniting with it; by assimilating it; by an interpenetration of it and ourselves. It gives itself to us, in so far as we give ourselves to it.” Underhill

The opera is the story of Jaufré Rudel, prince of Blaye, a troubadour, who devotes himself to a love that is unknown to him, except through his dreams and poetry. He relinquishes a life of privilege as this love becomes all that matters. His friends laugh at him for “changing and losing his sense of fun.”Jaufré responds, “Of all I have drunk, nothing is left, but an immense thirst. Of all the embraces nothing is left, but two clumsy arms.” He declares, “I will be seen no more.” His declaration proves to be prophetic.

Reviewers have observed that Jaufré longs for an idealized romantic love. That his quest to possess such a love is reckless and ends tragically. That may be, but this opera has deeper themes—ones that explore devotional love, the need to belong, and what is reality.

Devotional Love

In his dreams, poetry and songs, Jaufré begins longing for a devotional love… one to which he may freely offer himself, one to which he may surrender, one to which he may belong rather than possess, one which will bring forth sublime joy.

In a meditation entitled Amid the Chaos, Sister Wendy Beckett says,

“To know what matters and what does not is the lesson that we long to be taught.”

Jaufré seeks to learn this lesson. He leaves behind living in the world of prejudices and labels that he and his companions created from the whole cloth of their own experiences.

Jaufré has an exchange with his companions that suggests he is reimagining what matters and what is possible. He says to his companions that there is a woman who is “so far away, that my arms shall never enclose her.” He sings that she is “beautiful without the arrogance of beauty, noble without the arrogance of nobility, and pious without the arrogance of piety.” His companions retort, “Such a woman does not exist.” Jaufré’s heart knows otherwise. Though his love lies far away, beyond reason or common sense, it creates indescribable joy when he devotes himself to her in his poetry, songs and dreams. This joy is what he seeks.

A Need to Belong

Jaufré’s longing for this distant love grows from a desire to unite with it, to belong to something beyond himself and what he knows. He has no words for it. He cannot uncover it conceptually. He seeks it intuitively in his dreams and writing poetry and songs. With unexpected help, he takes new steps in his journey towards it.

A mysterious pilgrim arrives and intervenes, singing, “Maybe she does not exist, but maybe she does.” The pilgrim, like a heavenly angel, suggests to Jaufre the possibility, as Underwood says, of “uniting” with his distant love. He says he saw a woman across the sea in Tripoli who possesses the qualities he described. Jaufré’s interest is piqued for a moment, but he returns to his dreams of a pure love that is free of worldly entanglements, and worthy of selfless devotion. He cannot yet imagine more than his dreams.

In the middle acts of the opera, the pilgrim sails back and forth, from one shore to the other, between Jaufré and Clemence, the Countess who embodies his desire. He gains their confidences and guides them with great tenderness. Clemence, offended at first, soon opens to the poetry of Jaufré’s devotional love. The women of Tripoli caution her, “Neither good company, nor sweet embrace, neither marriage, nor land, nor children. What good therefore can distant love bring?” Clémence, however, is letting go of desiring love that is transactional. She, too, longs for a love that lies beyond her worldly experiences.

When the pilgrim tells Jaufré that Clemence knows about him and his poems and songs of love for her, he is stunned. He decides he must go to her. Jaufré sings, “I can no longer think of her without thinking that she too watches me from afar.” It is no longer enough for him compose songs she will never hear.

He and the pilgrim set sail for Tripoli. It is a literal and figurative crossing over. The voyage illumines the true nature of Jaufré’s love and shakes him to his core. In exaltation, he sings, “This is my second birth. At the end of the voyage my life shall begin.” But, he also grows fearful. He sings, “I’m afraid pilgrim. I’m afraid of not finding her, and I’m afraid of finding her. I’m afraid of dying, pilgrim, and I’m afraid of living.” Jaufré is confronted with the prospect of living groundlessly, knowing while not knowing. It is neither an easy or sure transition for him. His inner turbulence reflects the turbulence of the sea. It becomes destabilizing. His journey increasingly carries great personal risk, real and imagined, inner and outer. He soon falls ill. In spite of it all, he continues. He sails without hesitation because he has uncovered what matters. Underhill says it this way, “Some great emotion, some devastating love, beauty, or pain lifts us to a new level of consciousness.”

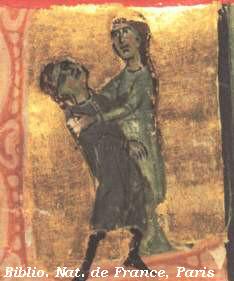

Waiting in Tripoli, Clémence is also conflicted. She both hopes for and dreads Jaufré’s arrival. When he lands, Jaufré is carried to her on a stretcher. He is dying. As they meet and speak for the first time, they confess their passion and pledge their love to one another. Jaufré’s fears vanish. He fully embraces all that is unfolding. As he lays dying in Clemence’s arms, he sings, “The last sensation of my mortal body is that of my worn-out hand that falls asleep in the hollow of yours. Even if I lived another hundred years, how could I know a joy more complete? In this instant, I have all I wish. Why ask life for more?” He knows with utter clarity that he belongs to the love of his devotion.

Clémence holds his motionless body for a moment. She then stirs to anger and begins to rail against God. A chorus repeatedly urges her to be silent. She shifts the blame for Jaufré’s death to herself. She is overwhelmed by the pain of her loss. Suddenly, without words of explanation, without considering or planning what to do, she vows to go into mourning and hide herself away.

Critics have argued her quick decision is not believable.

What is Reality?

Jaufré and Clemence both thought they knew. Reality seemed to arise from all they could see, from their experiences and their resulting beliefs. For each of them, things occurred that cracked what they regarded as solid, foundational. They responded by opening to it rather than fleeing or retreating. At such moments, we are able to glimpse a greater reality. Our imagination and desire to know can lead us to it, but we must experience it for ourselves.

Ayya Medhanandi, a Theravada nun recently wrote

“The pain of the heart is a cracking open. It’s a complete cracking open. It’s a seeing, it’s a bearing with.”

Clemence is seeing. She is seeing that her way forward lies in the direction of withdrawing from the distractions of the world.

As if she were already in a convent, she kneels and begins to pray. It is unclear to the audience to whom she is praying, Jaufré or God. With her prayer, the opera ends and her journey towards an inner reality begins. She steps towards what Underhill has described as “a passionate communion with deeper levels of life than those with which we usually deal.”

She sings: “If you are called Love I adore only you, Lord, If you are called Goodness I adore only you Lord…. My prayer rises to you who are so far from me now, To you who are so far. Forgive me for having doubted your love, Forgive me for having doubted you! You who gave your life for me, Forgive me for having remained so distant. Now that it is you who are distant, Are you still there to hear my prayers? Now it is you who are distant, Now you are the distant love, Lord, Lord, you are love, You are the distant love..”

(Curtain)

It is now Clemence who desires a love that does not spring solely from her life, but from somewhere afar. She longs for the complete joy of which Jaufré spoke. The poet, Rumi, describes this joy in his poem, Moving Waters. He writes,

“When you do things from your soul, you feel a river move in you, a joy.”

Clemence has heard the sound of its rushing waters.

![]()

Offered with gratitude

Zhong Fen li Bao yu Di

Monk in Training, A Single Thread Contemplative Order

Image Credit: http://www.tripoli-city.org/amour/synopsis.html