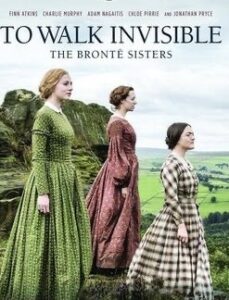

“To Walk Invisible” is a television drama that first aired in 2017 about the three Brontë sisters, Charlotte, Emily and Anne. The story tells of a period in their lives when they are transformed from sisterly supporters, financially dependent on their aging father and their only brother, into independent successful writers.

The Brontë family, housed in the large rectory of the church where their father is the parson, live together but apart, each family members’ life unfolding behind the many closed doors of the old house. It is a dark, somber and spartan domestic scene. Each of the three sisters and their brother (Bramwell) secretly struggle to make sense of their lives within the structure of family values they unconsciously share and unwittingly uphold.

Bramwell is celebrated within the family as the one with creative genius who will be famous. The sisters all face advancing age, dwindling prospects for marriage and few prospects for employment. The Victorian culture of the day affords them no ready options other than dependence on their brother to carry them on the shoulders of his success. Yet Bramwell is descending into alcoholism. His prospects for fulfilling the family’s expectations are dwindling as well.

As these pressures in the Brontë household mount, the closed doors of the house begin to open. Bramwell’s drunken stupors, which he has kept hidden, are revealed to the sisters as they dare to open his door and enter his world. The sisters leave their private spaces to encounter each other in the shared regions of the house. Here they begin to speak their feelings in whispered conversations, having previously limited their discussions to the business of their lives. They gather in pairs, never all three together, not yet trusting a wider audience of three, to begin to say out loud that which they had not yet dared to name. Failure. Addiction. Depression. Aging. Anger at the sublimation of women into intellectually inferior roles, though they know they are not intellectually inferior to men.

In the realm of my interior spaces, I too have encountered the closed doors of addiction, my deepest fears and failures, the aspects of life that do not fit the identity I had always assumed for myself arising from my history, my community and my family. I too have stayed busy with making a life, keeping the doors closed on all that did not fit the look and feel of the world I knew. But the life I was making, like the Brontë’s, was based on a plan with deep cracks, riddled with inconsistencies.

Spiritual work, like the artistic journey of these women who would become some of the world’s most respected authors, begins…and continues…with opening doors. To make great art or to cultivate Buddha Mind, one begins by naming that which is hidden. “Turn around the light to shine within,” * says the ancient text. To shine the light of awareness, to tell the truth of how life is not conforming to our hopes and dreams and find the courage to name it: In “To Walk Invisible,” this truth-telling is the tension-filled opening story line of the two-hour drama.

The impetus to open doors arises primarily from the sisters’ consternation with Bramwell’s drinking and his inability to hold a job. Bramwell drinks to escape from the pressure of his role in the family. A heavy mantle of the successful artist has been placed on his shoulders. The expectations have cultivated in him the pride and prestige of a Victorian gentleman. His failure to live up to this expectation brings a shame he cannot bear to face. He turns increasingly to debilitating drinking, all the while insisting he remains on the road to success. He self-medicates and blames others in order to bear the pressures of this delusion.

Addiction to work and to intellectual prowess have kept my disenchantment with my life from overtaking the drive to keep going, to not give up on the grand plan ordained and blessed by family, friends and culture. Like Bramwell’s Victorian way of life, my energy of disappointment with and resistance to a 21st century lifestyle lies buried beneath the deliciousness of the pride I take in being a smart and successful modern woman.

Also, like Bramwell, I have taken comfort in blaming any number of others for the suffering I feel: parents, family, spouse, the social system, my culture of origin. But mostly I blame myself. My struggle with pride and shame is reflected in the portrayal of Bramwell, who is pridefully angry at his family and so privately ashamed of his failures that he is unable to take responsibility for his plight. It is humbling to see myself reflected in Bramwell’s resentment toward others, combined with aggression turned inward. It is revealing to me that it is his own pride and shame that keep Bramwell from moving out of the system that holds him.

Feeling forced by others is a potent form of impotence. Zen teaches me to see the pride in the blaming, to see the damage it has done, and to let it go, without substituting shame in its wake. I am learning to recognize that I am neither a God or a demon, neither enviable or pitiable, neither a victim nor a perpetrator, but able and willing, with the help of so many forces in the universe who proclaim the Truth, to follow a path of the teachings.

The sisters see that they have escaped the most dangerous intensities of pride and shame because they are considered nobodies within their social structures. Such a paradoxical gift it was to them, to be nobody! The humility of “nobody” takes dedicated practice to realize when one begins from the inner perception of a “successful” life. Buddhist training includes regular examination of all the ways a student intoxicates herself and the further instruction to drop these poisonous barriers to Buddha Mind.

In my practice I am facing how I intoxicate with the deliciousness of constant thinking, planning, figuring things out, of being the one who knows. As I let these thought patterns go, it becomes more apparent that striving for intoxicating intellectual dominance has kept pride and shame running, kept me bound to a mental-emotional, familial and social system that hides a deeper truth.

To see the Brontë sisters’ capacity to abandon social conformity is an inspiration. They are not captive to the successes they claim as members of the culture because there were few rewards and benefits for single women like themselves. This gives them freedom. Relinquishment of my pride and “status” is my ticket to great freedom as well.

The Brontë sisters further empower themselves by their refusal to blame Bramwell for their plight. Despite their fury at him for lying, cheating, fighting and stealing his way through his descent into alcoholism, they know that Bramwell has been under tremendous pressure to be what his family needed him to be. They see what it has cost him to live with the expectations of his family to which he was so ill-suited. “I’m so glad I’m not HIM,” Emily declares, speaking with empathy of the multiple pressures to succeed he has had to contend with. Their compassion carries all three sisters through the scourge of the alcoholic disease as it progresses in their beloved brother. Throughout their own changing relationship to power, success and creativity, the three sisters take care of their failing sibling, protect him from knowing too much of their mounting artistic successes and tenderly respond to his immediate needs when he is at his most undone by the disease.

The Brontë’s compassion helps me to relinquish blaming myself for my addictions and shaming myself for my failure to better manage the pressures to conform. Watching the sisters, moment by moment as they move from trying to save Bramwell to simply caring for him opened me to the possibility of forgiveness for my perceived inadequacies. It is a relief when I can forgive myself, and in the forgiving to open to “failure” as a good teacher. My instinct to feel shame about my strategies for coping with a system that I could not bear is further unraveled when I see that Bramwell’s suffering is the impetus that drives the sisters out of their delusional family identities, even while their brother cannot bear to open this door. I appreciate that the pain of too much delicious and poisonous thinking, too much dependence on knowing-it-all made for enough suffering that I could begin to let it go. And in the letting go, I see the larger system of false beliefs and values that drove me to intoxicate.

As they share their pain and their inspirations with each other, the sisters argue and resist each other’s ideas as much as they take comfort in their sharing. They are terrified of the unraveling family fabric and what it means for them. It takes strength to name out loud the failures of a system we always counted on to hold us, create meaning for us. The Brontë women are my wise older sisters, showing me the Way with their courageous and determined relinquishment of old ways of being. Yet their courage is not without uncertainty and trepidation. They are deeply hesitant to risk what Charlotte is the first to name out loud: That their writing, which all four siblings have together practiced since childhood, is the sisters’ ticket out of poverty.

There are many threads to be unwound as the conversation between the sisters takes shape. Charlotte confesses to Anne the escape from their personal misery that her writing has afforded her, an escape into fantasy and lore. Together the two sisters acknowledge that to feel most alive in their writing they must turn away from fantasy, the subjects of the stories they wrote as children, to writing the truth of women’s lives. My own writing as spiritual practice has often reflected the fantasy of I Know, I Am Somebody, I Have the Answers. Seeing these fantasies in my writing, I am shown where blindness to childhood ways continues to hold sway. Here too the Brontë sisters inspire me to keep going, to keep seeking a way to write that is fresh, alive, that tells the truth of this path, this world beyond the visible, the understood.

But the risk of failure is great. Emily names the fear they all feel of exposure to ridicule for daring to imagine that their writing could be published, and would sell. Women in Victorian England were rarely published, and when women’s writing was brought to print, its authors were subject to the ridicule and hostility of Victorian men. The tension around how to move forward becomes the subject of the sister’s first three-way truth-telling. It is an explosion into open fury, kindled when Charlotte steals into Emily’s room to read the poetry she has written and hidden away. Emily is livid, strikes out at her older sister, disgusted with her actions and her grand publishing schemes. Charlotte is unrepentant. Emily’s poetry has taken her breath away. As Charlotte steals her first reading of her sister’s work, we the audience hear the exquisite poetry as a voice-over while we watch Emily walking the twisted paths and steep hills of the moors outside of the town, far from the constricted world of her home life. We see her as a part of the wide, open world through which she moves, stretching to where earth meets the sky. We breathe more deeply to see her here, sensing the freedom that is coming for the sisters.

Anne is the careful, thoughtful middle sister, brokering between her two head–strong older siblings a continued openness to what is unfolding. She quietly finds a way to keep naming the truth of writing’s power to bring great joy and aliveness into their difficult lives. Eventually all three are captivated by the creative energy they experience in the act of writing of the human experience. They begin to let the aliveness of it propel them forward, now sharing as three the nourishment, the truth they find in writing, the possibility of using their stories and poems as a means of having power in the world.

Turning the light within, opening long-closed doors to reveal the darkness and pain there and the instability it can create, the explosions that can result, this is the muck of life that holds gold within it. As the sisters tentative sharing eventually leads them to shaping their new reality, so too the consistent practice with naming and studying all the various manifestations of one’s desire and aversion allows a Zen student to drop the delusions, letting go over and over of all the goods and bads, the failures and successes she holds to so tightly so that a third possibility can emerge.

Letting go, so unbearable at times, becomes easier to trust as one tastes the freshness of life out beyond the tired painful dualities of old habits of mind. For the Brontë sisters, this spacious brightness is first revealed in Emily’s poetry. Her compositions, uncovered by Charlotte, are the force that propels the three women to write secretly, invisibly, and then to publish a small volume under an assumed (man’s) name.

On a spiritual path, the work too is in secret, invisible and driven by deep love for the possibility of finding that which is true, that which is not accessible within the realm of family and social values. The sisters “walk invisible” so that their creative energies can be protected from probing, judging, doubting minds. Minds that still cling to the old ways, the mind that remains within them and outside of them, the mind that insists they stay put in the known. They are beginning to see something that is all around them, but visible only to them. They are charting a new course, telling a new story. These are possibilities one must relinquish the material world in order to see, just as the Brontë sisters had to relinquish the Victorian social order and their dependent roles in a family system in order to write in a completely new way about changing women’s lives.

As the story draws to a close, the three sisters finally share with their heart-sick father, whose son they all now openly acknowledge will not be who they hoped, that they are the true authors of published and widely heralded novels. Written under pseudonyms, Emily has authored Wuthering Heights, Charlotte Jane Eyre and Anne Agnes Grey. All three novels, but especially Jane Eyre are already immensely popular. The books occupy a central shelf in the Brontë home, yet the sisters have remained anonymous until this moment in the film. Their disclosure is compelled by their wish that their father know they have been transformed under his nose, they have become three people who he does not know and could not have imagined. It is a tender moment, a moment of great tribute to walking invisible.

In the end, what mattered to these, my older sisters, was that they found a way to write, found words that no one before them had found, to speak a truth no one before them had spoken, of the world in which they lived. The successes of their novels bespeak of readers hungry for these words, hungry for that which they, too, were on the cusp of knowing but didn’t know how to say. And after all the publishing and accolades and re-printings, the sisters were still “nobody.” They navigated the stormy waters of their Victorian world without resentment and reached the other shore, without celebration. And kept walking.

Lao Huo Shakya

ZATMA is not a blog.

If for some reason you need elucidation on the teaching,

please contact editor at: yao.xiang.editor@gmail.com

*Accessed 10/13/2019 from https://www.asinglethread.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/A-Single-Thread-Chant-Book-rev-2.pdf#page61