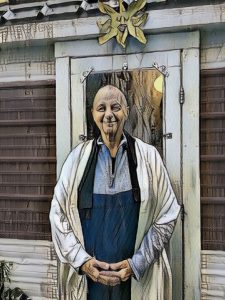

The following letter is written by Lao Huo Shakya, a monk of the Contemplative order of Hsu Yun, to her father, A. Erik Gundersen, M.D. (retired). During a long and illustrious career, Dr. Gundersen was a surgeon specializing in cardiac, thoracic and pediatric surgery at the Gundersen Clinic in La Crosse, Wisconsin. He pioneered the new technique of open-heart surgery in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s and went on to build a thriving regional center for heart surgery within the institution that was founded by his grandfather in the 1920’s.

The Monk.

Andrea Gundersen often went on hospital rounds with her father on the weekends as a school girl, and as a young adult, she watched her father perform open heart surgery. Though fascinated with her father’s medical world, she initially resisted entering into the family business of healthcare. Eventually she entered the field from another angle altogether, training in the new science of body-mind integration through mindfulness, movement, talk and touch. She and her father have long debated the relative merits of western vs. traditional and holistic approaches to health and healing. In the 1980’s they together read a philosophy of integrative medicine, which led to him inviting her to lecture before Grand Rounds on the emerging science of trauma as a body-centered phenomenon, and the alternative therapies that can treat it. Through the decades, this conversation between father and daughter and between paradigms of healing has periodically surfaced.

When Andrea shaved her head, put on a robe and became Lao Huo Shakya, the dialogue between father and daughter went underground. As an avowed atheist, a scientist dedicated to the observed world as the foundation for what is true, the physician was surprised and befuddled by his daughter’s seemingly strange turn towards being a monk in the world he could not understand or appreciate. Recently however, their ties have found a way back towards the realm of thought and word.

The Letter to the Physician After a 90 Day Retreat

Dear Dad,

As the 90-day silent retreat I was on this winter came to an end in mid-April, we were gathered at a family lunch when you asked me if I would describe to you—in 250 words or less! —what the retreat had been all about.

This seemed a tall order at the time, with family members and dogs, plates of sandwiches and the brand-new experience of not wearing masks all swirling about. Nevertheless, it is a wonderful question. Allow me to answer it now.

Well, you already know that from agitating for a recycling center when I was in high school to organizing unions to providing therapy for trauma survivors, I have gravitated toward work that I hoped would contribute to ending the pain and anguish of humanity and the planet. But I came to realize that there would always be more suffering than I could ever relieve. My individual suffering alone seemed hopelessly intractable. It was all wearing me down, with no end in sight.

The wisdom tradition that began with an ordinary human named Gotama Buddha also has suffering as its primary focus. Rather than respond to suffering by going outward towards activity, this unbroken lineage of teachers and students have practiced turning inward to investigate how the mind itself produces suffering. A primary conclusion of this 2500-year investigation is that suffering arises when we want things to be different than they are.

In this way of seeing things, to be human is painful and difficult from the moment of birth until our last dying days. This is what it means to be human. Of course, we do what we can to alleviate the pain, for life is very precious and we have a lot to learn while we are here. But the bottom line is to accept that life is going to rub us the wrong way! It is a surrender, an opening into a higher consciousness, within which the absence of suffering is found. Maybe you have seen this in very sick people, the ability to find a place of rest, even joy as they contend with their failing bodies. This is another central tenant of Buddhism, that suffering can end.

When I discovered these fundamental propositions in my late 40’s, it lit a fire within me that still burns bright. The possibility that always drove me, that suffering can end, was not a delusion after all. It remains the worthiest of efforts, worthy of spending three months in silence and sequestered from family and friends so that it could be my singular focus. Such a retreat is like being in graduate school, or writing a novel, where everything else is set aside. It is devotion, in this case, to paying full attention to all the experiences of my days and nights from brushing my teeth to taking a walk to contending with hip and shoulder pain to eating a meal—everything. Within each activity I studied how my mind grabs for what it wants as if it were what I need, the many ways I find to be anywhere else but present to the only moment that we actually have to live in.

I realized that so most of what I want is selfish, I have SO MUCH, plenty! I saw a well of hatred and arrogance from which my frequent judgements and criticisms arise and spill out, causing more suffering. I realized how quickly life is passing by, that in a flash it will be over. I saw that every word I speak and every action I take has a lasting impact. I am tremendously grateful for these insights; walking in this way through the fire of my own suffering I am warmed by the light of a larger truth out there beyond right and wrong, beyond even birth and death. In THIS place fear falls away, I am safe, all is well.

And here I am, having used up more than twice the number of words you requested. Be careful what you ask for! And—thank you for asking, it has been my pleasure to tell you this tale of my winter’s work.

With best wishes for your well-being as summer approaches, A.

Author: Lao Yuo Shakya

ZATMA is not a blog.

If for some reason you need elucidation on the teaching,

please contact editor at: yao.xiang.editor@gmail.com