A Father’s Birth

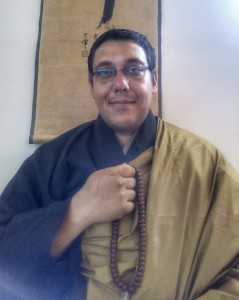

A series of articles on becoming a parent from a Zen’s priest memories, guts, and imagination

Click here to access all available issues of “A Father’s Birth”

Part 2: Vespers in the night

Still in Crete, we went down to the village and walked across the square and faced the entrance of a small church. The sound of hymns and the scent of incense floated from its open doors, inviting us to enter. We could see that there were flickering candle lights inside the church; but outside, standing in the moonlight, we both felt that strange sensation of kensho, of being between two worlds.

We entered the church and something unimportant caught my attention and I precisely lost… my attention. I drifted past the icons at the entrance, nodding an homage, and then I became aware again of the church. It was very old, but well preserved with beautiful ornaments and murals painted on the walls. My wife was getting a little tired, so we sat in a rear pew.

Suddenly a change in the liturgy occurred. A group of men, local farmers, formed a circle around a high rotating table on which was placed an open book of hymns. Each man took his turn to step forward and sing a part of the hymn in his own style, reading the text or reciting it from memory. We could see that the men’s role in the ceremony was central – their expressions were not the fake piety we often see in paintings – but were rather like the expression of a messenger who has to convey important information. Every few moments in each man’s recitation, he’d glance up at one of the icons as if the message was meant specifically for the spiritual entity that had inspired the artwork. It was as if something inside the man was singing to something inside the statue. I knew that feeling. Often when chanting “Amitabha” – sometimes letting it sound like “Ah-mi-tow-fo” – I’d stare at a statue of the Buddha Amitabha and my voice did not seem to be my voice, but just a sound made by someone inside me that was meant for the marble or the brass to hear.

Behind the main altar, a curtain separated and a man clad in a long ceremonial robe and golden kesa appeared. The words of the hymn seemed to change, as if they were cues to make a certain mudra, chant a certain line, or strike a certain bell. The man, who I assumed was the head priest or, as one villager called him, “the pope,” became an integral part of the whole. The singing circle of men and the man in ceremonial robes could no longer exist without each other. And then the liturgy ended. A blessing was given and the people began to disperse.

It was late and I knew my wife was tired. We had done a lot of walking in the mountains and it had felt good to sit down in the church, especially in that strangely holy atmosphere. We were glad we waited to the end of the ceremony.

As we stood up to leave, one of the men who had been in the circle, spoke to us in English. He welcomed us and explained a few things before he could introduce us to “the pope” who had just removed his golden chuddar or kesa from around his neck. He reverently kissed it and folded it just as any Zen priest would have done with his rakusu or kesa. I watched him and it occurred to me that he was now completely alone… or at least alone with his God. And then I remembered something my grandmother used to say: “Religion is what you do when you are alone.”

The priest approached us with a silent calm, and then he noticed my wife’s swollen belly and he smiled broadly and picked up the wooden cross from his rosary and held it against her belly, whispering a prayer. Then we began to talk. He spoke a bit of English and some words of French that one of the men who had chanted could assist in translating if we needed it.

He asked if we were Orthodox and I told him that I was a Zen Buddhist but that I respected the Orthodox way and knew it quite well because I had practiced in small retreats that had been founded by Hesychast Orthodox monks from a French community associated with an Athonite monastery. Athos, or Mount Athos, is a sacred mountain in Greece; and our conversation quickly began to talk about spiritual practices, the role of Silence, the wonders of repeating certain prayers. To the Orthodox Catholics it was particularly The Jesus Prayer, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner.” I told him that in Buddhism, although it could be expressed in slightly different ways, it was “Namu Amida Butsu” or “Namo Amitabhaya Buddhaya.” We both agreed that there was a inexplicable power that came from repeating these mantras. We also agreed on the meditative peace of Perfect Silence, the silence that comes when body, mind, and breath are in harmony. I quoted Lin Ji, that this state “Gives the mind what it needs to attain Oneness.”

Finally we talked about a modern saint I had come to respect from reading his works. The priest had met this saint several times at Mount Athos. We were speaking of Saint Father Paisos and the priest or “pope” and I became quite animated talking about him. We forgot all about the pregnant woman standing next to us. And then, perhaps because the candles behind her had burned down to a critical level, her shadow was cast on the wall. He and I noticed it at the same time. And he murmured that Mary must have looked the same as the shadow on the wall.

I thanked him and took my wife’s arm and we started to leave the church when he suddenly called out to us, “What have you named your son?” Startled, I said in a voice that was more question than answer, “Eliott?” It was the name my wife and I had recently decided upon.

“Ah yes,” he said. “Did you know that the village’s monastery is called, “Mouni Profiti Ilyas” (Monastery of the Prophet Elyha). Elyha is the root name of Eliott. He added, “You should both visit the monastery and the monk who is in charge of it.” He blessed us and we thanked him and then got in our car and drove to our little inn in the hills.

During the drive, I began to wonder about odd coincidences. What in the world had made us decide to name our baby Eliott? My wife and I both live in Belgium and our main language is French. Eliott isn’t a common name at all here where we live. It was, at best, I had thought, a name we heard on a TV sitcom or in some movie. There were hundreds of names we could have chosen. I knew the name of Saint Father Paisos, but I had not associated it at all with any monastery. As to Athos, that name is well-known as one of the Three Musketeers. We both would have steered clear of giving our boy any name associated with an adventure story. It would have been like calling a child, “Clark-Kent” or “Samson.” So I cannot answer what has become a koan to me. Why did we choose the name Eliott?