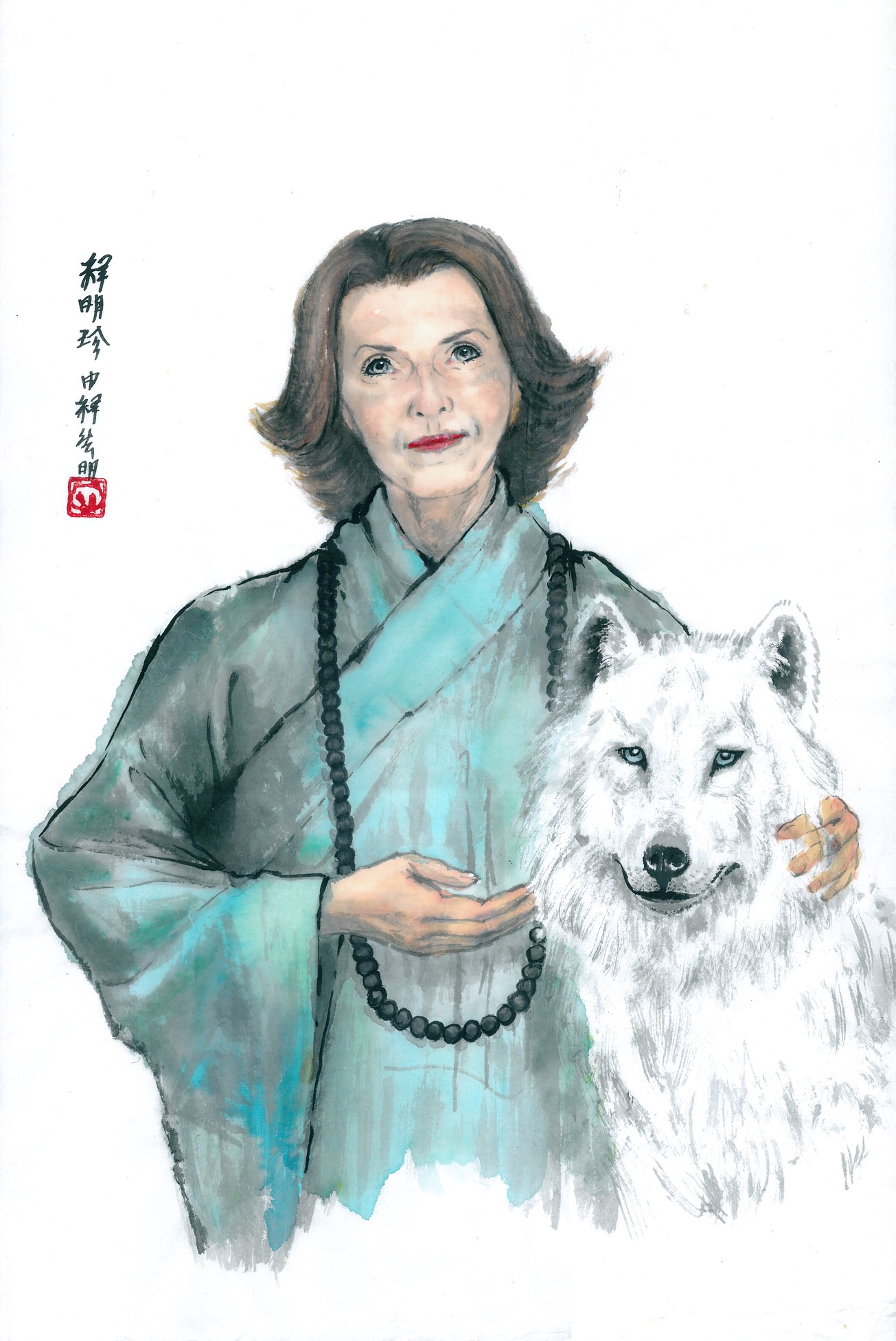

by Ming Zhen Shakya, OHY

Archimedes was stymied. The greatest mathematician in the world had a problem that baffled him. How could he determine whether an intricately wrought crown was pure gold or gold adulterated with a base metal? He knew what a given quantity of gold should weigh and that the same quantity of adulterated metal would have a different weight; but how could he determine the quantity of material in the crown? He couldn’t cut it up into measurable pieces. What to do? What to do?

As every troubled thinker does, Archimedes decided to take a hot bath. And it was then, as he sank into the water and the liquid sloshed over the sides of the tub that the concept of displacement occurred to him. Two things cannot occupy the same space. He might not have been able to measure the space the crown occupied by measuring the crown, but he could easily measure the amount of water the crown displaced. He could quantify the material! Jubilant and still naked, he ran through the streets shouting “Eureka!” I have found it! I have found the answer!

How do we tell false from true and penetrate surface to probe core? Insight requires the hard work of disciplined thought and observation; and most of the time we’re too tired, or lazy, or distracted to bother. So we laugh or gape or, if we do feel an emotional response, we look at the reflection of what we’ve projected onto the surface and coo adoringly or cast the glancing shadow of our own malice; but usually we see nothing but what it suits us to see. We don’t care to look behind the mirror.

From the trove of oriental wisdom comes a famous parable which illustrates the meaning of dharma, the nature or natural order of a thing, the design ‘plans and specs’ to which the thing conforms. Regardless of any superficial characteristics it may present, everything has its dharma, its true, interior nature.

In the parable, an encounter between a venomous creature (a scorpion) and an innocuous one (a holy man) is observed by an uncomprehending man who, though he thinks he understands what he sees, has no real insight. He cannot penetrate the surface to plumb the depths of meaning.

Several years ago, in his film, The Crying Game, Neil Jordan brought a version of the parable to the West’s attention: A soldier, while making love to a woman, is captured by rebels who hold him hostage. Hooded, his hands bound behind him, he is guarded by a calm and gentle man who tries to make him as comfortable as possible.

The soldier, fearing execution, plays upon the guard’s compassionate nature by evoking manly sympathies. By action and word he poses the Archimedian problem: what is our true nature? Are we what we appear to be?

On the surface they would seem to be opposites. Racially, one is black, the other white. Politically, one is a soldier in service to the ruling power, the other a rebel in arms against it. But underneath these surfaces, do they not share a common nature? Do they not love, play, joke, urinate, and do all things that make them human? Are they not equals? The captive displays a photograph of the beautiful woman he loves and asks the guard to visit her and to convey the final thoughts of his undying love. It seems little enough for a condemned man to ask.

But the soldier further attempts to compromise the guard, to seduce him with voluptuous praise. There are, he insists, only two kinds of people in the world: “those who give and those who take” – the implication being that they are both good ‘giving’ men who give because it is their nature to be kind and compassionate. “You will help me,” says the soldier, “because it is your nature to be kind. You won’t be able to act against your nature.” And then, to illustrate his point, he relates the parable of the encounter between a venomous and an innocuous creature, in this version, a scorpion and a frog:

A scorpion, desiring to get to the other side of a river, asks a frog to carry him across. The frog is reluctant because he fears that the scorpion will sting him; but the scorpion dismisses the possibility saying that it wouldn’t be in his interest to sting the frog since then they’d both drown.

“The frog,” says the captive soldier, “thinks it over and then agrees to the deal.”

But mid-way across the river the scorpion stings the frog who, shrieking in pain, asks the scorpion why he has done this; and the scorpion replies, “I couldn’t help it. It’s my nature.” The theater audience laughs. It’s a clever explanation… the divine blueprint, the genes and chromosomes of scorpionhood. Yes, the guard will likely yield to the imperatives of his nature and help the soldier.

But if we are seeking insight, immediately we are confused. There is a problem here. Neil Jordan has dunked us in the Archimedian tub. First, there is the flaw of contract. There has been no “deal.” What is the necessary consideration? What benefit would the frog receive from ferrying the scorpion across the river? None was stated. If we are to believe that he is acting out of simple kindness, why then is the guard’s adherence to his own nature being likened unto the scorpion’s? He is being asked to act as benignly as the frog, not as detrimentally as the scorpion. Something does not jibe. We sink into the bathwater and await enlightenment. In television’s small claim’s court program, Judge Joe Brown, we recently heard another version of the parable. The judge, after deciding a case in favor of the defendant, responded to the plaintiff’s claim that her faithless and irresponsible lover had unduly enriched himself at her expense, by turning to the camera and lamenting, “It’s always this way. A person falls in love with someone who keeps breaking promises and acting badly. But the person keeps on forgiving the bad conduct. And then, when the relationship finally ends, there’s the inevitable complaint of breach of contract. ‘I gave this and I was promised that…’ On it goes. It reminds me of a story,” the good judge recalls, “of the woman who finds an injured snake on the road. She brings it home and nurses it until it recovers. But as soon as the snake is healed, it bites her. She says, ‘How could you bite me after I did so much to help you?’ And the snake says, ‘Lady, you knew I was a snake when you brought me home.'” The spectators in the courtroom laugh. A snake can’t help being a snake. Yes, the woman’s got nobody to blame but herself.

But something is wrong with this scenario. And once again we are sloshing in water, trying to understand, squinting to see truth. Do we assist only those distressed persons who post a bond, who give us a surety, a guarantee of reward, or payment-in-advance for our trouble? What is the judge trying to teach us? That we should be indifferent to the sufferings of others or restrict our charitable assistance to those who are certifiably impotent? Wouldn’t we rather be the Good Samaritan and risk ingratitude – or worse, than be the kind of person who ignores a signal of distress?

Perhaps a look at the original parable will help to clarify the problem:

A holy man is sitting by a river into which a scorpion falls. Seeing the creature thrash helplessly in the water, the holy man reaches down and scoops it up, placing it safely on the ground; and as he does this, the scorpion stings him.

Again, the scorpion falls into the water; and again, the holy man rescues him and is stung for his trouble.

Yet a third time the scorpion falls into the water and is saved by the holy man; and yet a third time the scorpion stings him.

Standing nearby is a man who has been observing this indignantly. He approaches the holy man and angrily asks, “Why do you keep rescuing a scorpion that keeps stinging you?”

The holy man gently shrugs. “It is a scorpion’s dharma to sting,” he says simply, “just as it is a human being’s dharma to help a creature in need.”

In the holy man’s demeanor and his explanation, we understand the parable. He has acted without egotistic desire, without expectation of reward or compensation, without entering that realm of conditional existence that is, for a spiritual person, assiduously to be avoided. He has acted in perfect freedom, doing what he considers is the right thing to do, without fear of consequence because he knows that his happiness does not depend upon exterior events or eventualities. He is an individual, independent, needing nothing or no one. He is responsible only to his God; and because he respects God’s designs – all His blueprints for life, he acts without singling himself out for special consideration.

And this equanimity is possessed by the guard just as it is prescribed for the plaintiff.

In The Crying Game we’ll indeed discover that the guard is the counterpart of the holy man. He, too, acts innocuously, without contract, without expectation of reward. It is the seductive soldier who is the poisonous scorpion; and, regardless of how he promises to conduct himself, he will act in accordance with his own ego-nature’s self-interest. All his talk of brotherhood, of a shared, generous nature was calculated to manipulate, an allurement to conscience. It was not what it seemed to be. In fact, he has secretly untied his hands and, relying upon the guard’s sense of decency – which surely will not allow him to shoot a man in the back – he breaks free and runs away, leaving the guard to face summary execution for having allowed his prisoner to escape.

And then we recall… as Judge Joe Brown would have had us recall… that we had indications of the soldier’s character at the outset of the film. Didn’t we witness his infidelity in the opening scene? Wasn’t he betraying ‘the great love of his life’ at the time he was captured? And later, didn’t he lie and conceal relevant truth when he cleverly aroused the guard’s interest in the photograph? His faithlessness and duplicity were already a matter of record.

Judge Brown, in his examination of the Plaintiff’s case, also established this point. At the outset of the relationship, the evidence of character, of nature, was there; and the plaintiff chose to ignore it, preferring to see what she wanted or needed to see. Only in retrospect, was each gift of money a loan. But why, the plaintiff was asked, when the man had not repaid the first loan did she give him a second? And, when he also failed to repay that did she give him a third and put her credit cards at his disposal for the fourth and fifth, and so on. The woman had an ulterior motive, one with which we all can sympathize, but one that had nothing to do with business agreements. She wanted to be loved and appreciated. In fact her gifts were bribes, inducements to yield the love she sought. But her image of herself – and her explanation for her actions – was that she was a kind and generous person, one who couldn’t ignore someone’s needs. She said that she helped because it was her nature to help. But if this were true, why was she demanding repayment?

In the absence of any evidence of agreement to repay, the Judge had to find for the ungrateful defendant. And so he spoke of a woman who had nursed a snake and who had not been prepared to accept the consequences of snake-handling.

The soldier’s and the Judge’s version of the parable are not intended to explain anything. They merely serve to warn, to caution us against accepting self-serving assurances and self-gratifying suppositions – and never to discount dharma. Yes, we are free to help an injurious person as often as needed, and to forgive him as often as we wish; but we cannot expect him to reform himself in accordance either with our hopes or with his manipulating promises. We are not asked to refrain from helping a scorpion, but only to remember – to remain aware – that it is a scorpion we are helping.

And implied in this awareness is the need to determine why it is we are helping him. Did we profess kindness as a means of huckstering a holiness which, in truth, we did not possess? Did we require love and appreciation so much that we were willing to purchase it? Is our ego such that we imagined that we could convert a scorpion into a canary, a serpent into a lapdog?

And if it is true that we have lavished so much attention upon someone who was so unworthy, so snakeish, what does that say about our powers of perception, not to mention taste? The ego’s desires are like beads upon a mala, an endless concatenation of fondled expectations. If ungratified, we experience disappointment; if gratified, we drop the bead and palpate the next desire.

In a social context, if we act purely to help someone, we do so without quid pro quo arrangements. If we are repaid, fine. If not, fine. Where there is no contract, there is no remedy – nor need of one.

In The Crying Game‘s final scene, the guard, asked to explain his self-sacrificing nature, repeats the parable of the scorpion and the frog. But he does this entertainingly, without guile. He exaggerates the shriek of the frog and dramatizes the scorpion’s response. In perfect simplicity, unaware even of his own humility, he likens himself unto the scorpion. He can’t help his nature – which we know is unconditionally loving and expansive.

The plaintiff, upon whom humiliation has been imposed, will likely shrivel. She’ll no longer grovel for snake love, but we must suppose that until she can look within herself and discover her own egoless self-worth, she’ll continue to see reflected love or hate in those upon whom she has cast her imaged desires.

Archimedes did not allow himself to be deceived by appearance. He tasked himself with the hard work of achieving insight which required simply and monumentally that he solve a problem in measurement.

The crown was not what the goldsmith said it was. The metal was gold alloyed with cheap copper. In the process of ascertaining this, Archimedes had discovered a great, eternal truth.

With what joy did that old man run naked through the streets. ![]()