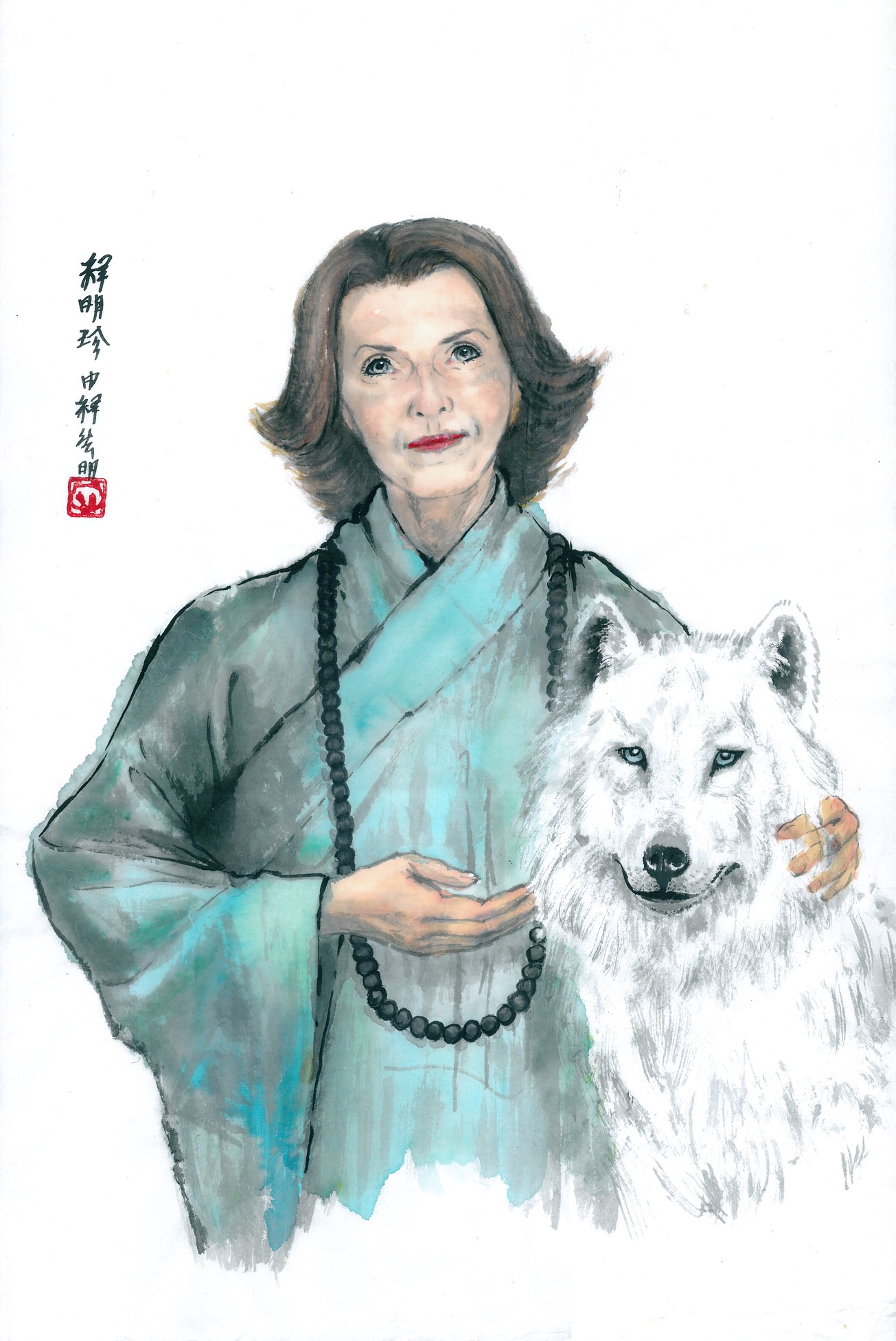

by Ming Zhen Shakya, OHY

Kanin, a professional hunter, was a good man. He was brave and reliable; and his skill with bow, net and spear was such that his reputation flourished even in lands he had never visited.

It pleased Kanin, but did not puff him up, to know that whenever an elephant or tiger was threatening a village, or whenever a visiting potentate required a guide to lead a sporting party, Kanin’s name – not the name of any younger, stronger man – would always be the first name called.

One day, while tracking a tiger into an unfamiliar part of the forest, high in the mountains, Kanin came upon an uncharted lake, a wondrous place, a hidden sanctuary that teemed with dazzling white birds. Incredulous, he blinked and rubbed his eyes; but they continued to identify waterfowl of every kind – heron and crane, goose, duck, egret and swan – and all in such profusion that he shook his head and giggled for many minutes before accepting his vision as genuine. Not even in legends or rumor was such a place as this mentioned.

“I believe that I see them,” Kanin shouted at the sky, “but how can I ever believe my good fortune?”

Proprietary thoughts began to crowd the hunter’s mind, for he realized that since it was unlikely that anyone else could know of the lake, all of its riches were his alone to exploit. “Why was I blessed with such a discovery?” he asked as he sat and marveled at the scene.

He could see the future clearly. “I need never work again,” he announced to the indifferent birds. “No more trekking through mud and brambles! No more insects and snakes! I have found enough wealth here to keep me prosperous for the rest of my life.” He would open a poultry shop, he decided, and every week he would come to the secret lake and take all the birds he could sell. Of course, great care would have to be taken to ensure that no one followed him! No one else could ever be allowed to know the location of his treasure.

His hopes for the future gave way to plans and plots and then to the deceptive schemes of secrecy – for he was a hunter and well understood the requirements of strategy, tactics, and stealth. Then, noticing his hunger, he roused himself and built a cooking fire.

Selecting a plump duck that swam nearby, Kanin drew his bow and took aim; but just as he loosed his arrow, the duck dived and the shaft harmlessly parted a few of its tail feathers. Annoyed, Kanin shot another arrow. This time the duck moved sidewards just enough to let the tip graze its breast. Again Kanin tried, and again he missed. Disgusted with himself, he tried to regain his composure “My excitement has put my aim off the mark,” he said, and he chose a larger target, a white swan. But again and again, his arrows struck nothing but water.

Out of arrows and furious with himself, Kanin resorted to his net. Carefully approaching some cranes that were wading at the water’s edge, he flung his net at them; but the birds quickly stepped out of range of the encircling net. Repeatedly Kanin retrieved and flung his net, but the birds always managed to elude it.

Trying to assuage his anger and frustration, he told himself that after all, his arrows and net were of a gauge suitable for tigers, not birds. The finest hunter in the world is dependent upon his equipment. He would simply have to return with finer arrows and a much lighter net.

Hungry and defeated and having neither the appetite nor the energy to search for rabbit or other game, he quenched the fire and turned homewards, carefully marking his trail as he went.

The next day at the marketplace he provisioned himself. He obtained new fowler’s nets, a tall backpack of wicker cages with a padded tump line, and the finest arrows the fletcher sold. Then he strolled through the marketplace and chose the perfect location to erect his poultry shop.

The following day, rested and equipped, Kanin followed his trail back to the hidden lake. The steep climb and heavy burdens slowed his progress and the sun was near to setting when he finally arrived. Yet the splendid sight renewed him. He could spend a lifetime, he thought, just trying to count the birds. “What good fortune!” he exclaimed. “What incredibly good fortune!”

Noticing the hour, he quickly made camp in a nearby cave, built a fire and then, with a quiver filled with fowler’s arrows, he strode to the water’s edge and took aim at the nearest birds. To his astonishment, his arrow missed the target. Again and again he tried, selecting other birds; but he could strike nothing but water.

Somehow, he reasoned, he was warning the birds. Some movement of his, imperceptible to him, was signaling them. He needed to observe their reactions more closely, but it was too dark to see clearly. Kanin retreated to his camp convinced that he had failed because he had hunted at a disadvantageous time. “I was exhausted from travel. My movements were clumsy. Tomorrow I will get up very early and then, when I am alert and the birds are still sluggish with sleep, I will kill one and capture many.”

He awakened before dawn and crept to the water’s edge. As soon as he could clearly discern a target – a sleeping duck – he shot at it; but the duck simply turned out of the arrow’s path. Kanin could not believe it. “What can this be?” he raged as he watched his arrow pierce only the still, cold water. “What black magic is this?” But though he seethed and fumed and repeatedly tried to strike a bird, he invariably missed. He also flung his nets, but they, too, entangled nothing but branches and water lilies.

He struggled to control himself, to find a cause for his failure. “I’m angry… furious… and the angrier I get, the worse my aim gets,” he reasoned. “Who knows better than I how emotion can confound the hand and eye?” When he regained his confidence and calm, he tried again. Still, he could not strike a single bird.

Dejected, he sat in his camp alternately cursing himself and his quarry until hunger nudged him, sending him into the thicket to hunt for lesser game. “Am I not known for my tenacity?” he asked himself. “Has any quarry ever successfully eluded me?” And he truthfully answered himself, “No. I brought down every elephant, deer or tiger I ever pursued; and I will bring these birds down, too.” He snared a rabbit, and as he roasted it, he formed a plan and waited for morning.

At first light he began to jog towards home. Not having to mark his trail or stop to eat, he moved quickly and was able to return to his village by early afternoon. Gruffly he dismissed his friends’ greetings and neighborly invitations. Nothing could deflect his concentration from its single- pointed goal.

The following morning, carrying all the equipment he needed to manufacture arrows, repair nets, and establish a permanent camp, he returned to the lake.

Though in the days and weeks that followed he shot hundreds of arrows, none ever struck its mark. Though he flung his nets hundreds of times, none ever settled upon a single bird. But his obsession was complete. Though exhausted and nearly maddened by defeat, Kanin continued to prowl the lake’s uncanny precincts, vowing that though he died in the attempt, he would capture the birds.

Several months passed. The hunter began to look and act like a wild man, crazed and brutish. His hair and beard grew long and tangled. He wore animal skins instead of tattered clothes. He snarled and grunted and the only words he spoke aloud were challenges and curses.

It was only when he sat near the entrance to his cave, at a point which overlooked the lake, and stared impotently at the birds that his expression betrayed his wild appearance. Only then did his face show that look of hopeless longing, that bitterness and sorrow which only human creatures know.

One morning as Kanin was beginning to stir, he heard a strange noise. A human voice! Someone not too far away was singing or chanting. Kanin crept out onto his lookout point. There, on the farthest stone of a row of stepping stones that extended into the water, stood an old priest; and all around him, nuzzling his legs, perching upon his shoulders, vying for the caress of his hands, fluttering, cooing, chirping and singing, were the damnable birds! Kanin winced in disbelief. He covered his face and bit his lip, then he crawled back into his cave and cursed himself more violently than he had ever cursed the

birds. But as the beautiful melodies continued to torment him, a scheme formed in his mind. Was he not a hunter?

Surely, he thought, the priest’s scent would be in his clothes. If he could only get those robes! He would shave his beard and hair and with pine boughs scrub away his own scent, and then dressed in the priest’s garments and singing the priest’s song, he would trick the birds.

Kanin returned to his ledge and studied the priest’s movements and memorized his song. “I hope you stay long enough to require rest, old man,” he whispered to the distant singer, and he added menacingly, “I also hope that you disrobe when you rest,” for Kanin had already decided that if necessary, he would kill to get the garments.

But the priest did not stop to rest. Instead, he simply bid the birds good bye, stepped back to shore and ambled into the forest.

Quickly Kanin left his lookout point, grabbed his knife and followed the priest.

The trail was difficult to follow. The priest did not go down in the direction of the villages Kanin knew, but instead moved laterally, over rocky ledges, until he reached the opposite side of the mountain.

For hours Kanin pursued the priest. Then, just before nightfall, he trailed him to his destination, a temple situated in a small and isolated town.

Kanin waited, hidden in shrubbery. He was sure that the priest, fatigued from his journey, would retire quickly. The old man would, of course, sleep soundly. Kanin would simply steal his robes and return to the lake. Fortunately, there was a full moon. It would aid escape just as the obliging night would discourage pursuit.

Unaware that a servant also shared the priest’s room, Kanin entered and reached for the robes. The servant, terrified by the intruder’s wild appearance, shrieked in alarm. Kanin struck him had across the face and, clutching his prize, ran into the forest.

On and on he ran until the cries of alarm dwindled into silence. Then he stopped; and after wrapping the precious garments in fern fronds to keep his own scent from contaminating them further, he climbed a tree. There, secured in the nook of a stout branch, he waited for morning.

At dawn, as he heard the distant temple bell summon the villagers to prayer, he continued to retrace his path back to the lake. He knew that he was being followed for he could hear dogs barking whenever he stopped to catch his breath or determine his direction.

Kanin moved quickly; but it was not until his pursuers stopped to eat their noon meal that he was able to gain safe distance. All day he travelled without rest until, near sundown, he arrived at his cave.

Quickly he began to sharpen his knife and to hone it finely to a razor’s edge. Then he lathered his face and head with the juices of marsh roots and shaved his hair and beard, carefully drawing the blade across his skin to remove the least stubble.

He entered the water and with pine bristles scrubbed his body until all his own scent had been washed away. It was dark as he dragged himself from the water and collapsed in exhaustion on the cold ground.

At the first light of dawn he was ready. He draped himself in the priest’s robes and, concealing a fowler’s net within the vestment’s folds, he followed the stepping stones out to the exact spot that he had seen the priest stand.

Kanin began to chant, his voice floating gently across the still water. Its unfamiliar sound captured his attention. How strange and beautiful, he thought. There was even an echo! Then, as he stopped to listen to the sweet reply, he happened to glance down into the water and was startled by what he saw. A face he did not recognize – a serene and gentle face – looked up at him from beneath the surface! Kanin gasped and the face also gasped. And suddenly Kanin realized that the submerged countenance was his own! “I’ve startled myself,” he confessed nervously.

Then, as he looked up, he saw in the distance a silver- ribboned waterfall which he had never noticed before. “Strange,” he said, “that in all this time I never even wondered about the source of the lake.” A peculiar feeling came over him. He felt as if he were just regaining consciousness after drugged sleep or a fainting spell. He squinted and rubbed his eyes.

Color began to fill his vision. Darting past him came a hummingbird’s iridescent green and the celestial flash of a bluebird. And there were roses by the lake… red and pink and yellow… and he detected their fragrance… and the fragrance, too, of honeysuckle vines that cascaded down the bank and into the water. How could he have missed all this? How beautiful this lake was… how the morning sun streamed down through the trees and glistened on the water… and the birds… how lovely they were… how innocent and peaceful. And suddenly an anguished cry rose up from deep within his chest and he covered his face in shame. “What a blind and ignorant fool I am,” he cried. “What a vile and savage brute! Oh, Lord, forgive me!” Tears rolled down his face and he raised his hands in a beggar’s gesture. As he extended his arms, the net slid from his shoulder and fell into the water. Then the water birds came to gather at his feet.

That night the villagers returned to the temple. “The thief got away,” the servant said. “We thought we had tracked him all the way to the lake, but he wasn’t there; and since it was getting dark, we turned back.”

“Oh,” inquired the priest, “then you saw no one?”

“Only a priest,” said the servant, “rather like yourself. He was kneeling in the water chanting the Buddha’s name.”

No one understood why the priest suddenly laughed. ![]()