A Father’s Birth

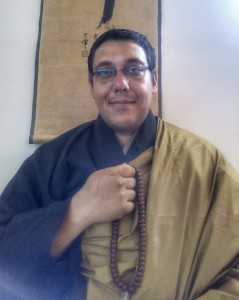

A series of articles on becoming a parent from a Zen’s priest memories, guts, and imagination

Click here to access all available issues of “A Father’s Birth”

Part 3: A Stained Bear in the Patio

Photo Credit: www.macedonian-heritage.gr

The next morning brought a blue and gold day. We had promised to visit Mouni Pofiti Ilyas and to speak to the priest there; and it was a promise we eagerly looked forward to keeping.

We were directed to a mountain lake and told that we could hire a boat and spend some time, just the two of us, on the surface of a blue pearl of a lake in the middle of Crete. We stayed on the water for an hour or so and then continued on to the church that the “pope” had recommended to us.

It was a huge disappointment. We stared up at the church that seemed to have been thrown together in no particular style, banal in the worst way, and half falling apart. A small 19th Century monastery sat grudgingly beside it. Why, we wondered, had the “pope” insisted on his particular monastery. “Probably,” I said, “he was proud of his village and wanted us to know it better.” The shame was that there were so many really beautiful and very well preserved spiritual sites all around us. “We may be wasting our time here,” I decided.

What we were doing, was “judging a book by its cover,” and this is always a foolish thing to do whether we are looking at people or old churches. The things in life that give us the most trouble are those things that we are too quick to dismiss or to overlook, regarding them as useless, unaesthetic, or unimportant. What we should have done was to be positive and trust in the old priest’s judgment – to look for that feature that was so special to him that he wanted us to see it. But instead we superimposed our own values on the building’s appearance and were negative and disappointed.

We walked around the monastery ground and finally found the main entrance, a very large metallic door. As I pushed on it I felt like a child pushing open a museum door. My wife encouraged me to continue, The sun was overhead and very hot and all I really wanted to do was to go back to the cool lake.

But we pushed the door open and to our surprise there was another door just inside the first one. This door was small and we could tell ancient. I had to laugh at our initial foolishness. We opened this interior door and found a lovely little patio – the flowered square that sits in the middle of the monastery complex. There were beautiful trees and flowers everywhere. “It’s like an Eden in here,” my wife said. And all around it was a high wall.

I thought about the habit we humans have cultivated since antiquity: constructing high walls that separate what is inside from what is outside. City states and the walls are our frontiers. Sometimes our homes have walls and guards that permit only the chosen to enter. In religion we see such walls too. They are supposed to enclose a sacred space. But the wall around the outside of this church was difficult to understand.

The interior walls were painted pure white and the sun’s effect on them made them dazzle and scintillate and, frankly, to hurt our eyes. I was still visually adjusting to the place when I saw a big black thing on a wall. At first I thought it was a hole in the wall and then the hole moved. It was a very tall and husky monk and he scowled as he stood up and looked at us. I knew without asking that this was the monk the “pope” said we should meet.

I could appreciate that monks must get sick of tourists who ask the same dumb questions over and over. But this monk was showing more than irritation at being interrupted in whatever it was he was doing. He glared at us and my wife murmured that she was uncomfortable being there. His black robe – which was much like our black ceremonial robes – had blotches of white all over it; and I realized that we had interrupted him while he was painting the wall.

He walked towards us, whispering something into his thick beard. I quickly told him that the village “pope” had sent us. He squinted a moment, doubting us perhaps, and then he told us to wait until he had finished painting the wall and had cleaned his brushes and tools. We waited in the garden, playing with a cat (there are always cats inside a monastery); and then

we walked around looking at the various architectural details that had been hidden from the street. The monastery was far more beautiful than we had imagined.

Finally, he came to us and quite rudely asked, “Before you enter,” he said, “I must ask whether or not you are Protestants.” We said that we were not and explained our backgrounds. He seemed relieved. “Zen,” I said, “Is the mystical path of Buddhism.” He looked at me as if to say, “I know that.” So I stayed quiet. I knew that there were centuries of old conflicts regarding the universality of God’s grace and the manifested energy of the divine. It’s sometimes difficult to imagine how what seems to be trivial is actually sufficiently powerful to split Christianity. In Buddhism we have similar splits about points that seem trivial to others. But I could tell that this priest neither needed nor wanted any comments from me.

Keeping our mouths shut, we followed the monk into the monastery church. Here, again, there were no Byzantine wonders to be seen. It was simply a nice 19th Century church – with one exception. The church displayed many fanions or banners, black and gold decorations that bore the double-headed eagle – which is the Mount Athos’ emblem. This monastery was then a sub-branch of an Athonite monastery, one that was outside the Athos peninsula. I didn’t know that such places existed and realized that the church had to be very special… very holy.

The emblem of the double-headed eagle signifies that the monks practiced “union and silence” throughout their everyday life.

We paid homage to the icon at the entrance, a beautiful icon of Elihya waiting for the coming of Christ at the end of times – which is, of course, similar to the way we await the coming of the Future Buddha, Maitreya. We also bowed before an icon of Mary carrying the Christ in glory, his head at the center of her chest – her heart chakra. Finally, we reverently bowed and acknowledged a variety of holy relics just as we would bow to a stupa. Finally we were directed to sit on a bench near the altar. We took out our Buddhist prayer beads, and silently repeated the name of the Buddha as we circled the beads through our fingers.

The big “bear monk” looked at us strangely. He was astonished by our respect for his icons and what he regarded as their Christian Orthodox practices. He came and sat next to me and said, “Keep repeating the prayer.” I thought this was strange but I did as he asked. Then he said, “You need to be diligent in your practice, more effort is needed.” Now I was clearly confused.

Here was an Athonite monk giving me a critique of a Buddhist practice. He saw my confusion and explained, “Saying the prayer isn’t enough. A prayer has nothing to do with just repeating words.” My own master had often reminded me of not falling into the trap of self-hypnotic trances by getting lost in a mantra. I was not succumbing to that hypnotic attraction, so I looked at the monk, wondering what he was trying to teach me.

“When you pray” he said sternly, “you must keep humble and attentive. When you pray you must pray for all the world, just as when you confess your sins, you must also acknowledge the sins all human beings make, and pray for them, too.” I was really stunned by these words since they could have come from the founder of my own Zen lineage: Ummon or Yun Men. He always insisted that students practice attention in all things they did. Every moment, every action is a mirror of our essential oneness with others. This was the mindfulness, this realization of not being someone who stands out, but is rather humble, a member of the whole of mankind.

The monk pointed at my wife’s swollen belly. “Baby’s name?” he asked.

“Eliott,” I said, and his face lit up joyfully. Suddenly he was not the grumpy, grudgingly tolerant monk I thought he was.

“Eliott’s father and mother,” he said buoyantly as he jumped up, “you come with me.” He led us to the entrance of another small building. He asked us to wait, and then he closed the door. We waited, admiring the simple but beautiful details of the wooden door. Finally he returned. His face was very serious and he carried a small gold cross in his right hand. “This cross,” he said, “is the one that the founder of our monastery always used. It had belonged to one of our saints. Do you wan to receive the blessing?”

I looked at my wife and saw that she was intrigued. We both cautiously answered, “Yes,” like children who are asked, “Can you keep a secret?”

The monk began to utter a few mantras that we did not understand, and then he blessed himself with the cross, just as an esoteric Buddhist would do before “entering the mandala” to establish the “Vajra Wall,” that would purify and create a sacred space.

He turned to me and rubbed the cross on the crown of my head and in the three dantiens, the three more important chakras (head, heart, hara). The he repeated the actions but in reverse, ending at the crown of the head. Finished, he indicated that I step back into the shadow of the church’s tower.

And then his face changed. He said the same mantras, but this time they seemed so full of meaning, as if he were not merely praying, but communicating with someone. He proceeded to perform what in yogic or other mystical traditions is regarded as “opening the channels and chakras” and “attaining the union of opposites in the heart. It looked like a Christian version of accessing the microcosmic orbit. My wife looked radiant as he blessed her and he, too, had that “other worldly” look of exaltation. And I knew that he was connecting with a saint… the prophet Elihya. It scared me a little to think that so much holiness was being heaped on my little son… as if he would be expected to become some kind of Buddhist saint.

Years before, at a crucial point in my spiritual life, my ass was saved by the Zen teachings I found in the Orthodox Christian teachings of the Desert Fathers. Through the Desert Fathers I was able to reconnect with Zen. I’ll always be greatful to Thomas Merton, Gregory Palamas, and an old summary of the Philocalia. But in that church at that moment, I realized that mystical traditions in all the great religions are the same to all true spiritual seekers.

A few days later, we were in the ancient capital, Hania, the very night of Orthodox Easter. All the parish church communities gather to prepare a big altar with an holy image which they surround with flowers and lights. All the church bells ring and everyone carries a candle.

I looked at my wife, her face glowing in the candle light, and thought about the the other living flame, the one that was in her womb. And then I remembered the priest’s insistence that I be humble and attentive and think not only of my child but of all unborn children. I felt a curious connection to the world. It was a very heavy thought! I tried to shake off that sense of responsibility to all children. Even though I knew it would haunt me, for the moment, I tried to brush it aside, and I asked myself, “Good Grief! What on earth are you going to name your next child?”