Hagakure (#6)

It is never too late to adopt the Samurai Way of Life, to abandon old selfish ways, to embrace new principles, and to devote one’s life to being loyal to those principles. Especially after a surviving a critical challenge to one’s existence, we experience a great need to find a better way of living, a code to live by that will impart indomitability to us. We are done with being weak. In her review of Jim Jarmusch’s film Ghost Dog, Ming Zhen Shakya shows one man’s conversion to the discipline of righteous beliefs.

Hagakure (#5)

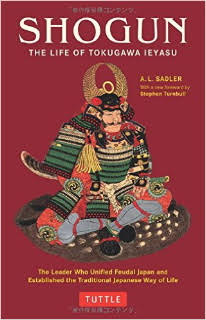

Firearms and Christianity brought new problems to Shogun Ieyasu which he solved by separation and division. When he died the Shogunate fell to his son and then eight years later to his grandson, the tyrannical Iemitsu. Forbidden to earn money and to spend months at court, languishing in boredom, most of the once-proud Samurai became poets, gamblers, fashionistas, gourmets, actors, gossipers, and womanizing drunks. Some, including Tsunetomo, who composed the Hagakure.

Hagakure #4

Conflict between North and South, introduction of firearms, and foreign religious interference present problems that only an extraordinary man could solve. The Shogun Ieyasu intended to be that man.To attain his goal he calmly resorted to force and political trickery. Yet one small betrayal wore so heavily on him that he wrote the Buddha’s name 10,000 times to atone for it.

Hagakure (#3)

Japan’s first “Separation of Church and State” long cherished by Americans was accomplished by its first Shogun, (“the barbarian suppressing Commander in Chief”) Yoritomo Minamoto who let the Emperor preside over religious matters in Kyoto while he moved the government, the first meritocracy, to Kamakura where he set the stage for the flourishing of Zen and the Martial Arts.

Hagakure (#2)

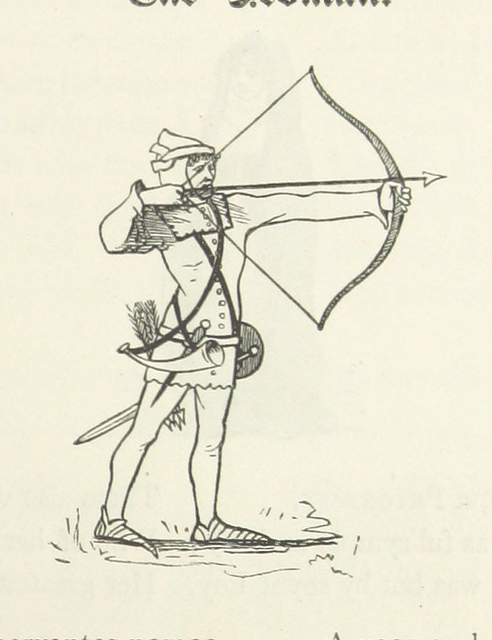

All great movements have a beginning which fulfills a need. Peasants, being given no armor or weapons when they were sent into battle, had to copy the “attack and defend” techniques of birds, insects, and animals. This became the beginning of Karate. In Part 2 of her Commentary on the Hagakure, Ming Zhen Shakya discusses how shifts in imperial power forced noble sons into the hinterlands where they became “servants” (samurai) of brutish warlords. They shed the foppishness of fashion and brought the ethos of unflinching loyalty to one’s lord, and this, mingled with the mastery of horse and weapon and the disciplines of Buddhist Meditation and weaponless fighting, became the root which had yet to send its stem up into the political world. This root would gather such strength that when it did break ground, it would define a civilization.